Remembering Gay Pioneer Bertram Schaffner

A boy caught between two worlds

Bertram Schaffner’s story is a unique one because of the multiple roles he played as a gay German American during the period that saw the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II. Born in November 12, 1912, to a German American father and a German mother, Bertram grew up in a nominally Jewish family that would celebrate major Jewish holidays but otherwise led a secular life in Erie, Pennsylvania.

His mother, Margarethe (Gerta) Rosenbaum Schaffner, had come to the States a few years before at the insistence of her father who wanted her to marry an American. Because of the circumstances of her arranged marriage, Bertram’s mother spent a great deal of her time travelling back and forth between the United States and her native Germany, bringing Bertram along for stretches as long as six months at a time.

In fact, he started his education in the local German Realschul. Bertram remarks in his testimony that throughout his young life, he felt that he lived between two worlds, neither fully American nor fully German. He also jumped three grades in school, graduating when he was fifteen. This experience contributed to his continued sense of disconnection with his peers.

After graduating high school, Bertram started at Harvard, a feat in itself during a time in which the university had a quota on the number of entering Jewish freshmen. At the time Harvard was still an all-male university, and fearing discovery of his homosexuality, Bertram Schaffner eventually transferred to Swarthmore in his sophomore year under the mistaken assumption that attending a co-ed school would help cure him.

However, the transfer to Swarthmore proved to open his world in ways he did not anticipate. It was during his junior year through a luncheon hosted by the college president that he met a visiting doctor from Central America, who would become his mentor and with whom he would have a relationship lasting two years. The doctor eventually convinced Bertram, who was studying literature and philosophy, to consider a career in medicine instead, a decision that would take the young man to John Hopkins, where he specialized in psychiatry.

(Read Swarthmore College's profile on Bertram Schaffner)

Rescuing his relatives while there was still time

In the midst of his medical training, Bertram traveled with his mother to Germany to visit his relatives but it was not like the usual trips they had made throughout his childhood. This was 1936, a time when it was already becoming clear to Jews living in Germany the growing danger of living under the Nazi regime.

Gerta Schaffner was on a mission to save as many of her relatives as possible. Armed with the necessary affidavits reluctantly signed by his father, Bertram and she traveled around Germany, visiting any city and village that they knew they had relatives: aunts, uncles, cousins near and distant. Gerta will eventually issue 70 affidavits to relatives who were then able to make safe passage to the United States.

As Bertram Schaffner notes in his testimony, each of his German relatives were able to hold their own in their new land without being a financial burden to his parents. His father had nothing to fear.

The Daily Impact of Paragraph 175

While in Berlin on that same trip, Bertram had firsthand experience with the impact that anti-homosexual policies had on German gays. He recalls stepping out while his mother was asleep in their hotel room, and making eye contact with another man in the park. The man stopped long enough to explain that talking to strangers was very dangerous. They could be arrested if they couldn’t prove a prior acquaintanceship and that there wasn’t a legitimate reason for them to talk with each other on the street.

Suspected homosexuals were already being brought in for questioning and having their rooms searched for any incriminating evidence. Their letters would be intercepted and read. Another witness in the Institute's archive, Albrecht Becker also talks about the interrogations he had undergone at a time when gays in Germany had enjoyed relative safety from persecution during the first few years of Nazi rule until Röhm's assassination during the Night of Long Knives changed their fate. It was the first time that Bertram came to understand at a very personal level the effect Paragraph 175 had on the lives of ordinary citizens now deemed “enemies of the state” in Nazi-controlled Germany.

Serving in the Military as a Gay Man in WWII

Bertram Schaffner, army photo from WWII

Bertram Schaffner, army photo from WWIISpecifically, he was supposed to help the military weed out suspected homosexuals. However, Bertram Schaffner took a very different direction. Instead, after establishing through a series of oblique questions if the draftee was gay, he would then determine what the draftee’s intentions in serving were. Officially, a homosexual was supposed to be dishonorably discharged from service, which would have created a record that would negatively impact the rest of his life. Schaffner, instead, would find another reason to honorably discharge a draftee that would allow the draftee a fighting chance in civilian life. There were also those draftees who, though gay, still wanted to serve in the military despite the policy. In those instances, if Schaffner felt they were otherwise mentally fit, he would approve their enlistment.

Screening draftees was tedious work, but a professor of Schaffner’s suggested that he could actually use this as an opportunity to gather a large data set about gay male sexuality. No one was studying that area at the time, and this could prove to be groundbreaking work. As Schaffner notes in his video testimony, not without a little amount of pride, the work did prove to be seminal, and that he is the only gay psychiatrist whose work is cited in the Kinsey Report.

Besides his time working for Selective Service, Dr. Schaffner also served in Patton’s army providing mental health triage for troops who broke down in combat. This work brought him close to the front line in France. He recalls one episode in which he and his patients were abandoned in a tent in the middle of a warzone when their division received orders to move on during the middle of the night. Finding dead german soldiers just outside the tent, he was afraid to venture too far away in case of landmines. Another recollection he offers in his testimony: he was also near the Battle of the Bulge when he found out that his best friend at the time was fighting in it. As a medical officer he had access to a jeep, though he was not allowed to drive it. Instead, his sergeant drove him in and out of German-occupied territory until Schaffner found his friend safe. His friend survived the war, and the two met up as recently as 1997 in San Diego, California.

Denazification and the Father Land

After the war, Bertram Schaffner’s military service was far from over. Through the Information Control Division, he worked on interviewing German citizens as a means of developing a profile of the national German character in order to understand what led to the rise of Nazism. He came to understand that it was not only the outcome of a specifically historical response to the socio-economic disarray in Germany after World War I but that it was also the result of a centuries long tradition of authoritarianism that was deeply rooted in German culture, starting at the patriarchal organization of the family. This authoritarianism helped doom the struggling Weimar Republic and needed to be addressed now after the war if Germany were to ever have a chance at enjoying a thriving democracy. The denazification process was seen as a very important step in the process of reinventing Germany as democratic nation.

U

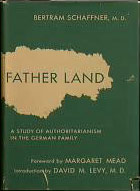

Cover of Schaffner's Father Land, with foreward by Margaret Mead

Cover of Schaffner's Father Land, with foreward by Margaret MeadHis work, however, ended up providing the initial research for his influential book Father Land: A Study of Authoritarianism in the German Family, published by Columbia University Press in 1948. It was revolutionary in its focus on a modern nation state as the subject for an anthropological study instead of on a primitive culture. It created an opportunity for him to work with Margaret Mead on a series of projects, including an anthropological study of the Russians. His book would also provide him entrée to do similar field work in the West Indies as part of a government effort to address the alcoholism crisis there. He eventually became the Executive Director for the U.S. Caribbean Federation for Mental Health, a position he held until 1968.

Gay Pioneer in the Medical Community

In 1982, Bertram Schaffner helped found the Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists of New York at a time when no psychiatrist dared to come out. In 1985, he was asked to treat patients with HIV at New York Hospital. He was one of the first to write about the treatment of patients with HIV and AIDS in an attempt to change the attitudes of physicians and nurses.

Dr. Bertram Schaffner passed away on January 29, 2010, at the age of 97, twelve years after he gave us his testimony in 1998.

You can view Dr. Schaffner’s interview in its entirety at vhaonline.usc.edu.