Hogan’s Heroes Actor Robert Clary, 96, Survived the Holocaust and Committed Himself to Remembrance

In September 1994, Hogan’s Heroes actor Robert Clary stepped up to be among the first 100 Holocaust survivors to be interviewed by Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, the organization established by Steven Spielberg soon after he finished filming Schindler’s List.

Then, just weeks after recording his own testimony, Clary volunteered to be an interviewer. Over the following 18 months, he interviewed 75 Holocaust survivors, helping the Institute seed a collection that would grow to include more than 50,000 testimonies by the turn of the century.

Clary, whose career included theater, radio, film and television credits, died Nov. 16 at age 96.

“Robert Clary gave a tremendous amount of time and energy to this unprecedented mission of collecting Holocaust testimonies, because he was so committed to honoring and preserving the voices of survivors,” said Robert Williams, Finci-Viterbi Executive Director of USC Shoah Foundation. “He was truly a master interviewer, guiding survivors through their memories with empathy and sensitivity.”

For the first three decades of his post-war life, Clary had little interest in sharing his story, including at the time he played Corporal LeBeau on Hogan’s Heroes—a 1965-1971 CBS comedy set in a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp. In fact, from the moment he returned to Paris in May 1945 after three years in Nazi concentration and labor camps, Clary refused to speak of his experiences, even with his surviving siblings.

“I was 19 years old. No self-pity. I turned that page so fast, it's unbelievable. I had one goal in my life. I wanted to go back into show business…And I just never wanted to talk about it,” he said in his 1994 testimony.

Then, in 1980, he watched a PBS documentary about a survivor who had gone back to visit Auschwitz with her son.

Then, in 1980, he watched a PBS documentary about a survivor who had gone back to visit Auschwitz with her son.

“And what she said in that documentary, that really woke me up,” Clary said. “She said, ‘You know, 30, 40 years from now, we're all going to be dead. And anybody can write anything they want about it.’... And I realized that she's right. After 36 years of not saying anything about it, I have to teach people about man's inhumanity to man.”

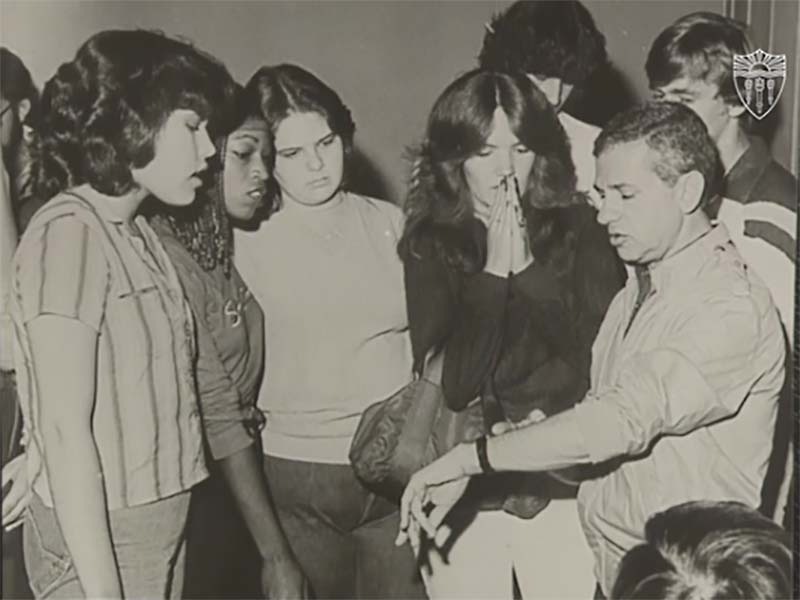

Clary began speaking at high schools and to community groups, and he volunteered with the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. He attended the first World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors in Jerusalem in 1981. And he became involved with Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, the precursor to USC Shoah Foundation.

In his 1994 testimony, Clary recalls a happy childhood that gave him both the tools to survive the war and the passion to make it in Hollywood.

He was born Robert Widerman on March 1, 1926 in Paris. He was the youngest of his father’s 14 children – six from a first wife, who died in childbirth, and eight from Robert’s mother. His father was a tailor from Warsaw who had moved the family to Paris in 1923.

The Widermans lived on Île Saint-Louis in an apartment building a philanthropist subsidized for Jewish families.

Clary describes a thriving social life in the building, where he enjoyed huge holiday celebrations with friends and family, played in a youth band, and benefited from mentors hired to lead activities and help the children with homework. At the age of 12, he began performing with a local theater and was featured on a radio show.

Clary describes a thriving social life in the building, where he enjoyed huge holiday celebrations with friends and family, played in a youth band, and benefited from mentors hired to lead activities and help the children with homework. At the age of 12, he began performing with a local theater and was featured on a radio show.

His parents kept him mostly sheltered from rising antisemitism, even after World War II erupted in September 1939.

France fell to the Nazis in June 1940, when Robert was 14. The family had their passports stamped with a “J” and were forced to sew yellow stars with the word “Juif” (Jew) onto their clothing.

With Nazis in power, Robert was thrown off the radio show and out of the theater troupe. But unlike many other Jewish children, he was able to continue his education because he was enrolled in a small private art school, not a public school. He recalls wondering if his friends would abandon him when he started to wear the yellow star.

“And the complete opposite. … The first day I wore the yellow star, they walked with me from the school to my home so that, you know, in case somebody does something, they're going to protect me. And I will always remember that,” he said.

In 1941, he witnessed Nazi soldiers rounding up and arresting Jews who were not French citizens, including some of his Polish-born family members. In September 1942, Nazi soldiers arrived at Robert’s apartment building on Île Saint-Louis.

Before being taken with his parents and other Jews to a local police station, Robert tied up his belongings – his comic books, his movie magazines, his art – in a blanket. The group stayed there overnight and were then deported to the Drancy transit camp, from which they were put on cattle cars.

At a stop along the way, men of working age were ordered off the train. Though Robert was 16, he looked 12. (As an adult, he reached the full height of 5-foot-1). Still, he managed to stick with the men, though it meant leaving his mother.

He later learned the train continued to Auschwitz, where his mother was killed in a gas chamber.

“A lot of people say, how come you didn't escape? How come you don't rebel?” Robert reflected in his testimony. “It's a dumb question to ask, really. If we knew that we were all going to go to the gas chambers...then of course we would rebel. It doesn't matter if we're going to die [in a rebellion], because we're going to die anyway. But if we don't know that, life is precious in a way…You want to live as much as you can.”

Robert was imprisoned in Ottmuth, a concentration camp that was a satellite of Auschwitz. He was sent to work in a factory, putting rubber heal taps on wooden shoes. To keep up his morale, he sang while he worked, and before long was summoned to perform song-and-dance routines for camp commanders. In his 19 months at Ottmuth, his voice and charisma saved him from deportation, earned him extra bread and soup, and brought joy and relief to the other inmates.

In May of 1944, Robert was transported to Blechhammer, another satellite labor camp of Auschwitz.

He was shaved, tattooed, given a striped uniform, and sent to work in a factory making synthetic fuel from coal. He also performed in two shows for the SS every Sunday, sometimes playing comedic women’s roles, sometimes slipping in a subversive Yiddish song.

"You entertain, but you're going to starve and you're going to die,” he said of the absurdity of his situation. “They can kill you in a second.”

In January 1945 the area came under bombardment from Allied forces, and Robert was among 4,000 people marched to the Gross-Rosen labor camp. Half the group was killed during the 15-day death march, and many more died under inhumane guards once they arrived at Gross-Rosen.

After three weeks he was again evacuated, this time to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. There, two French prisoners and a Czech camp secretary took an interest in Robert, who was by then frail. They got him moved from the Jewish barrack to the slightly less oppressive barrack for political prisoners. One of them ran an orchestra, and he recruited Robert to sing.

“They nurtured me back to life. They gave me food. They had sugar—that's the first time I saw sugar since 9 September 1942,” Robert said.

Allied planes flew overhead on April 11, 1945, and, with Nazi guards already on the run, Robert lay down on the roll-call field with other inmates to form their bodies into “SOS.”

A week later, he sang at a concert for American GIs.

A week later, he sang at a concert for American GIs.

By May 4, 1945, he had arrived at Hotel Lutetia in Paris, where his sister Cecile was waiting for him.

“We were crying like I’ve never cried before,” he remembered.

She told him that his parents and four sisters, along with several nieces, nephews, and other family members, had been murdered. Other siblings were finding their way back home.

Robert immediately turned toward the business of living his life.

He began performing at Paris nightclubs, where he was spotted by an American film and television producer who brought him to the U.S. In Los Angeles, he was taken under the wing of actor Eddie Cantor, and subsequently landed parts in theater, film and television. In 1964, Robert married Natalie, Cantor’s daughter, and in 1965 was cast in Hogan’s Heroes.

He began telling his story in 1980, leaving thousands of students with a message of empathy and activism.

"If you want this world to be alive, to be a fertile world, you have to stop feeling superior to another human being just because that human being has a different color skin, or different shape of eyes, or a different religion than yours. Do not feel superior to this person,” he said he told school children. “Give them as much chance that you want to have.”

Watch Robert Clary's full testimony in the Visual History Archive.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.