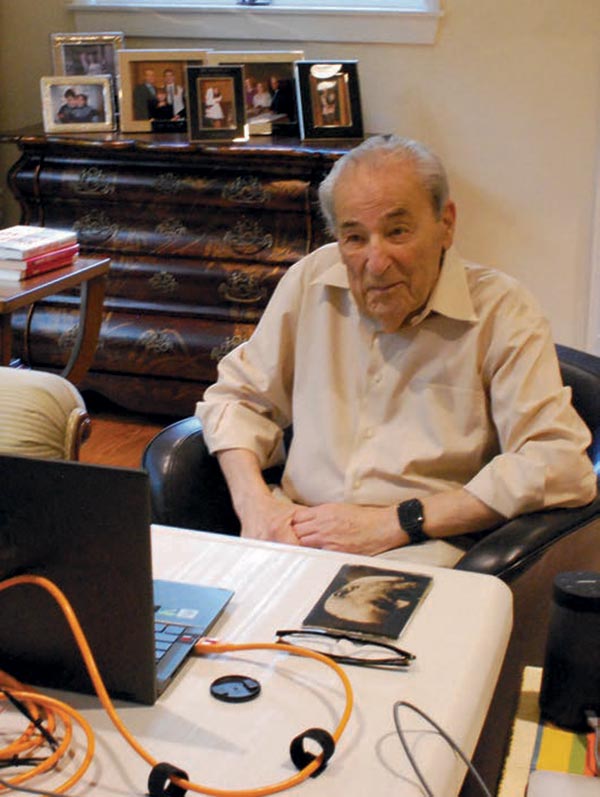

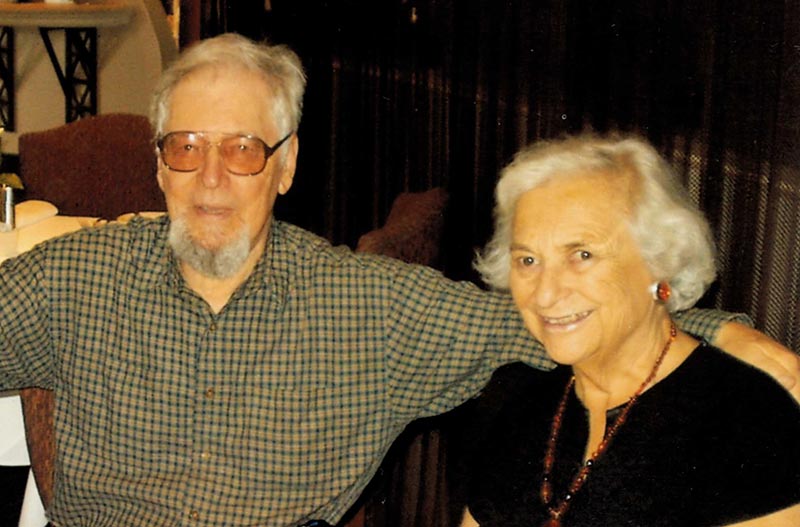

Like many Holocaust survivors, Joe Adamson had been reluctant to speak of his experiences, which included a series of relocations brought about by the rise of Nazism: from his birthplace in Koenigsberg, Germany to Frankfurt Oder to live with his grandparents—whose house was ransacked on Kristallnacht—and then to England on the Kindertransport when he was 14, arriving at Weston-at-the-Sea with a small suitcase and no knowledge of English. Later, he worked as a translator for the U.S. Army on a team that interrogated Nazis and was at the front with troops who liberated Mauthausen.

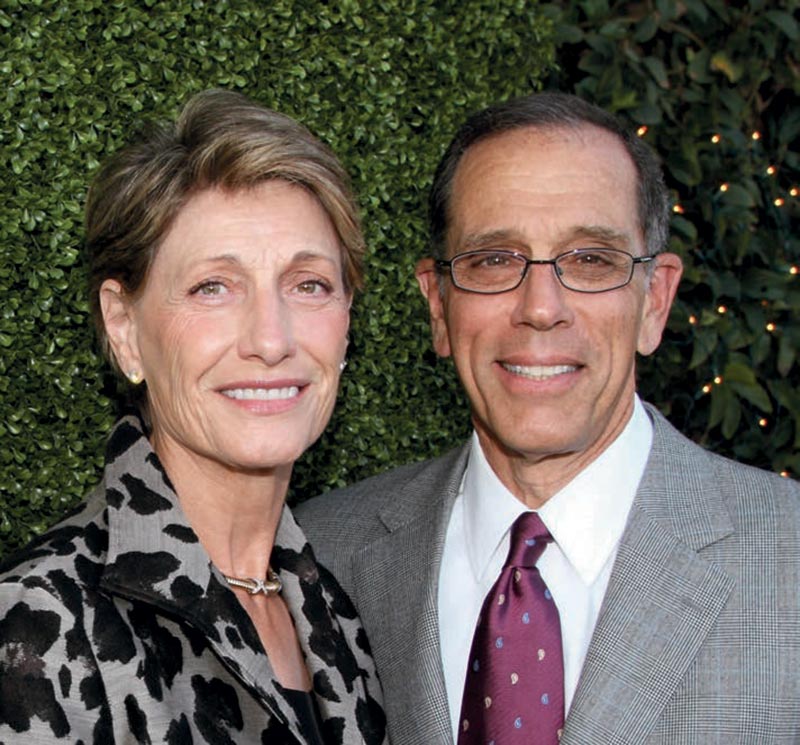

In her philanthropic pursuits, Andrea Cayton has made a point of focusing on education, supporting institutions such as the Cayton’s Children Museum and Holocaust Museum LA. By focusing in part on “education about humanity,” according to Cayton, she and her family hope to help children “learn about the past and be more tolerant.” When it comes to issues like prejudice and hatred, Cayton believes it’s “harder to change older minds. But if you start young, you are more likely do so.”

Elisabeth Citrom bears a sense of responsibility in telling her survival testimony: “I have a duty to share my story for the next generations to hear, in the hope they will get something from it.” Born in Romania, she survived the children’s barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau and was taken on a death march to Lenzing, where she was eventually liberated by Americans in 1945. She then lived in Israel where she served as an officer in the Israel Defense Forces before settling in Sweden to raise a family.

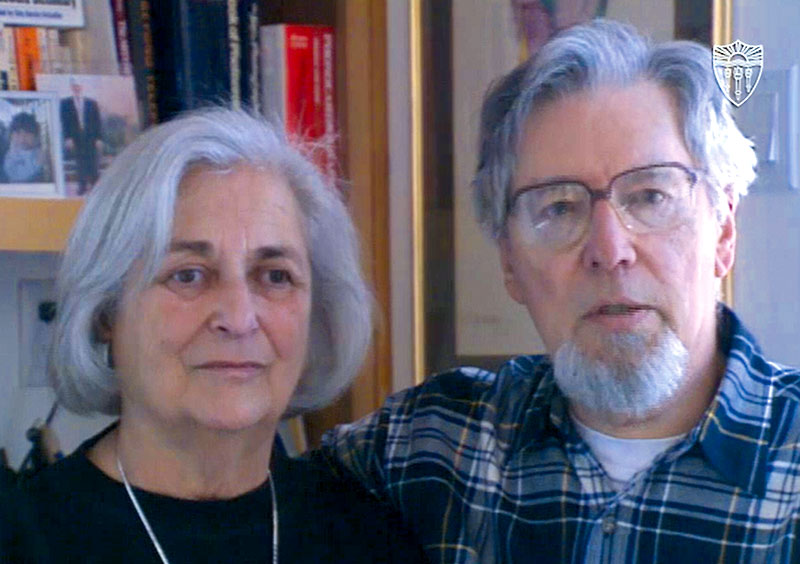

Board of Councilors Life Member Jerry Coben can pinpoint a moment that highlighted the importance of his involvement with USC Shoah Foundation. During a discussion with his son David about family history, David mentioned how much more meaningful he found the personal writings of Jerry’s mother compared to a detailed family history written by a cousin David had never met. The difference, according to Jerry, was that David could “hear” his grandmother’s voice in her writing, having known her well, something that wasn’t the case with his cousin’s narrative.

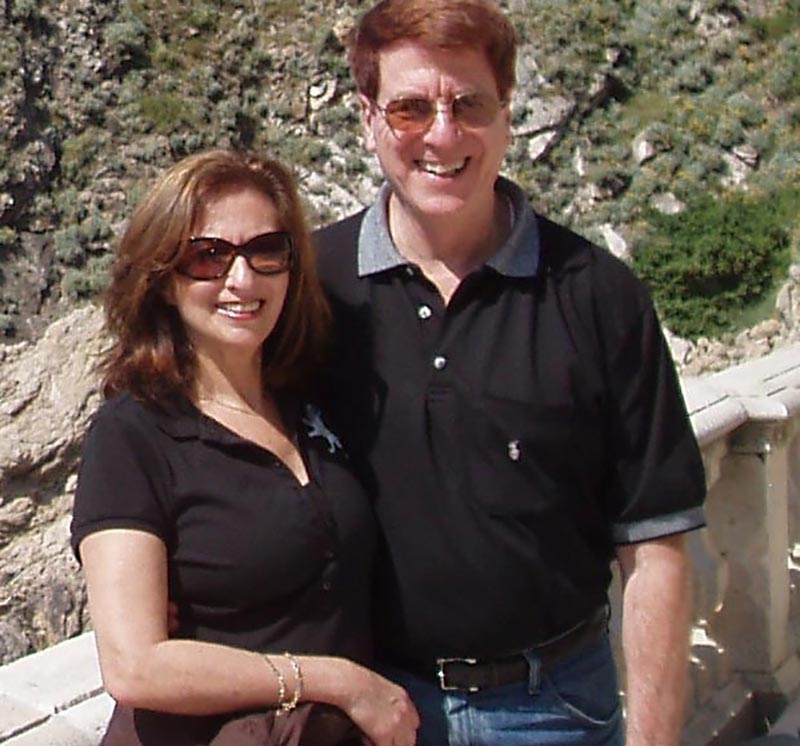

After being introduced to USC Shoah Foundation 15 years ago, Tamar Elkeles and Larry Michaels became invested in continuing the work of preserving Holocaust survivor testimonies. Many of their own relatives were killed in the Holocaust, and they keenly felt the responsibility to carry the torch for future generations.

Glenn L. Felner was just 18 years old when he joined the Army during WWII. “There was an undercurrent that I recall that Jews don’t fight, that Jews are cowards. So, I had to make a statement…I wanted to prove that Jews do fight…and to get as close to the action as I possibly could,” said Felner of his enlistment, which led to a wartime experience that would see him awarded with the Combat Infantry Badge, the U.S. Bronze Star and the French Legion of Honor decoration.

Holocaust education remains vital—as a means of understanding the horrors of the past, and for addressing contemporary antisemitism and combating the forces that lead to genocide. Echoes & Reflections stands as one of the premiere sources for Holocaust education and professional development in the United States. Formed by a partnership among USC Shoah Foundation, Anti-Defamation League and Yad Vashem, Echoes & Reflections has reached more than 85,000 educators since its founding in 2005.

Ruth: A Little Girl’s Big Journey is a short, animated film produced by USC Shoah Foundation. The film follows Dr. Ruth Westheimer’s early life, with Dr. Ruth’s own voice recounting how she survived the Holocaust as a young girl. According to Executive Producer Jodi Harris, the film gives viewers “a chance to discover much more about Dr. Ruth’s childhood and learn how she emerged from tragedy stronger than before.”

Partnerships are crucial in saving the accounts of Holocaust survivors and sharing them widely. Via USC Shoah Foundation’s Preserving the Legacy Initiative, Gabriella Karp, a Holocaust survivor, along with her sons Gary and David Karp, forged a three-way collaboration in which USC Shoah Foundation digitized and preserved more than 1,000 testimonies recorded through the Holocaust Memorial Center (HMC) near Detroit and the University of Michigan-Dearborn Voice/Vision Holocaust Survivor Oral History Archive.

Next Generation Council member Aliza Liberman’s philosophy for philanthropy is simple: “If you feel connected to a cause, you should get involved.” Liberman’s connection to USC Shoah Foundation comes from her upbringing in Panama, where her paternal grandfather immigrated from Poland to escape the Holocaust, in which his entire family was later murdered.

Though he did not know about USC Shoah Foundation until attending an Ambassadors for Humanity Gala years ago, current Next Generation Council (NGC) Co- Chair Thom Melcher was drawn to the Institute’s work upon learning of its mission at the time—to end hatred, bigotry and intolerance. Calling the Institute’s approach to education through testimony “the best way to create lasting change,” Melcher relished the chance to be active in the fight against hatred.

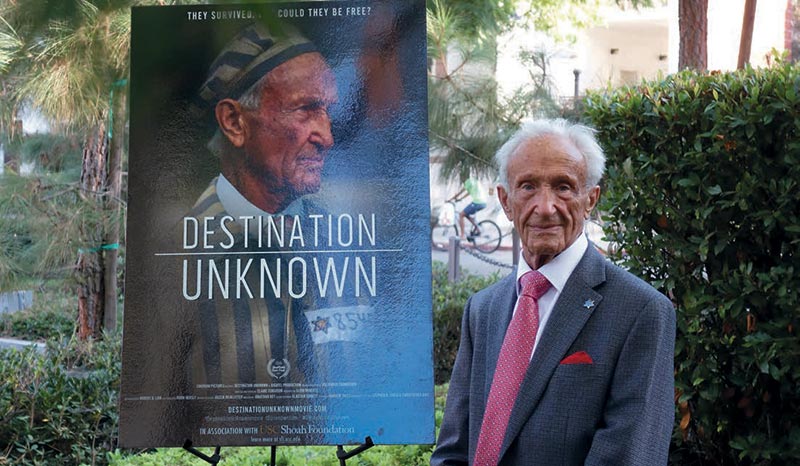

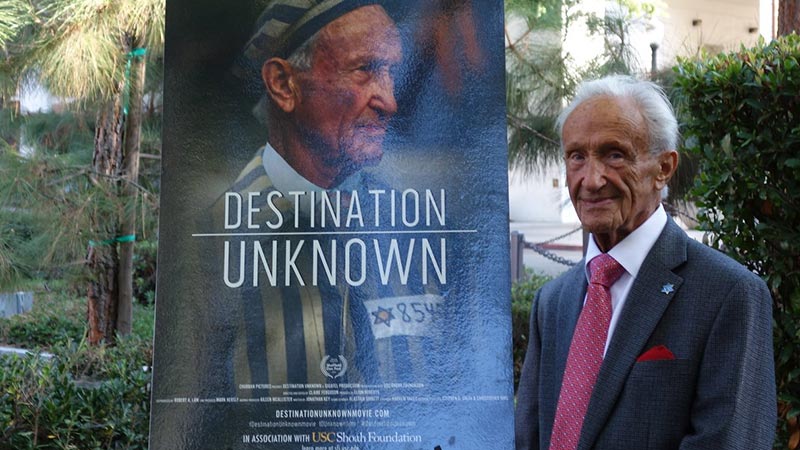

Holocaust Survivor Ed Mosberg has not slowed down. At 95, he’s dedicated much of his life to the tireless work of sharing his story and preserving the memory of those lost, which includes more than 60 of his family members. “I lost my whole family,” Mosberg said, “and I have to ensure that their story will never be forgotten.”

Growing up, Nancy Shanfeld was disturbed by the stories her mother and aunt told of facing antisemitism as some of the only Jewish children in their south Saint Louis neighborhood during the 1930’s. “Imagining these incidents still breaks my heart,” Shanfeld said of the harassment and threats her mother Mignon Senturia and aunt Ruth faced from children and adults alike. Though Shanfeld did not experience much direct antisemitism as a young person herself, hearing of the hatred and prejudice faced by her mother and aunt moved her greatly: “It was two little girls against the world.”

In 1933, when Ilse-Lore Delman was six years old, she was kicked out of her school in Frankfurt, Germany, for being Jewish. Intuiting the threat of the growing Nazi movement within the country, her family fled for Holland in a furtive dash, leaving behind all their possessions. After a few years of peace in Tilburg, Ilse and her parents were forced into hiding after the Nazi invasion of Holland.

In October 1942, when Nathan Drew and his wife Helen heard rumors that Nazis would liquidate the Łomźa Ghetto in Poland in which they lived, they escaped to Warsaw, avoiding by mere hours the forced removal of over 8,000 Jews to the Zambrow transit camp. In Warsaw, Nathan and Helen used false identification documents to live in the open as “counterfeit Poles,” hiding their Jewish heritage while navigating the harsh realities of Nazi occupation.

Throughout the nearly 150 interviews she conducted of Holocaust survivors for USC Shoah Foundation, Nancy Fisher’s philosophy was simple: “I did my best to be a human being connecting with another human being.”

When Nancy Fudem and her son Jonathan were contemplating ways to honor the memory of Nancy’s husband Frank, a prominent San Francisco commercial real estate broker who passed away in 2012, they considered some of his lifelong passions: family, education, and his Jewish faith. His wide range of interests, from spy novels to economic theory to Talmud study, indicated a deep and curious mind that valued the power of knowledge. “Frank credited much of his success to his start as a scholarship student at York Country Day School, and was always passionate about education,” Nancy said.

Like memory itself, the video testimony within the Visual History Archive is not permanent. Data degradation resulting from the gradual decay of storage media can result in the eventual breakdown of video and audio, rendering a testimony worthless, even in digital form. The Institute’s newly-launched Forever Fund will provide means to ensure that testimonies will live on in whatever form the future may necessitate.

For producer Richard Hall, supporting USC Shoah Foundation’s efforts to collect testimony related to the 1994 Genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda is a natural extension of his work as a documentary filmmaker. “A good interview really connects you to the humanity of others. We are all the same, but we don’t really feel it until we have the chance to bridge the language barrier and understand context for another’s experience.”

For USC Shoah Foundation Next Generation Council member Jodi Harris, contributing to the Institute is a family affair: Her mother was a docent at the first iteration of the Institute in the mid-1990s, leading tours of the trailers in which the Institute was initially housed on the backlot of Universal Studios.

When Marc Haves was growing up during the ’50s and ’60s in the Five Towns, a predominantly Jewish area on Long Island, one subject didn’t seem to come up during family gatherings, or in the history lessons at school, or even during conversations at his reform temple.

Thanks to an extraordinary gift from the Koret Foundation, USC Shoah Foundation is partnering with the Hold On to Your Music Foundation to develop an educational program centered around The Children of Willesden Lane, a novel and musical that highlight the story of Jewish children rescued from central Europe and sent unaccompanied to Great Britain by the Kindertransport at the start of World War II.

Alive through oil and acrylic, the eleven survivors of Auschwitz look forward resolutely, facing the world together, bound by their shared history. The survivors are subjects depicted in an 18-foot wide portrait that served as the centerpiece of artist David Kassan’s recent exhibition Facing Survival: David Kassan at USC Fisher Museum of Art.

Sam Pond, a member of USC Shoah Foundation’s Next Generation Council, has been a firm advocate for the Institute since being introduced to its work almost 15 years ago. “I’m not Jewish, but I hate hatred, and dislike ignorance,” Pond said, discussing his draw to the Institute’s work. “People don’t really understand how insidious antisemitism is. It’s growing worldwide, especially in the West.”

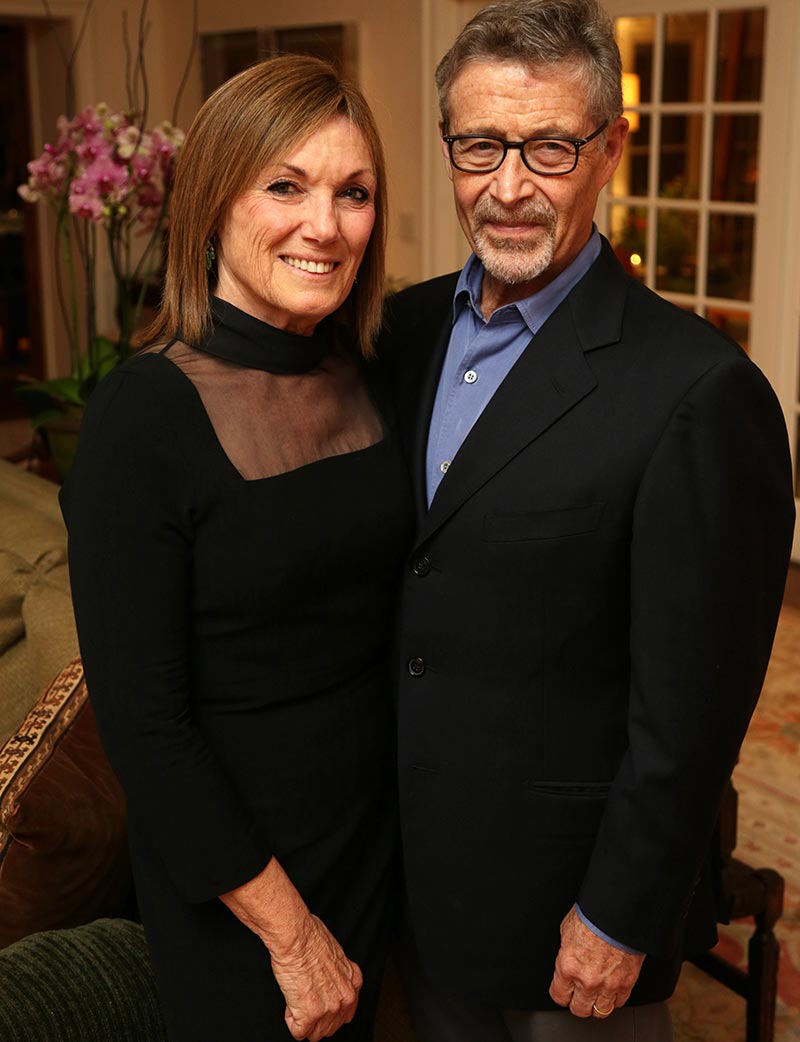

As a longtime donor to USC Shoah Foundation, Pennsylvania-based The Snider Foundation has supported a variety of Institute programs, including the Countering Antisemitism Through Testimony initiative. According to Jay Snider, President of The Snider Foundation, “Our Dad [founder Ed Snider] grew up in the shadow of the Holocaust, and the survival of the Jewish people was of utmost importance to him.

Like many who support USC Shoah Foundation, Linda Wimmer was drawn to the stories of survivors and the way the Institute gives their stories both a home and a platform from which to be shared. However, her connection to the Institute is more profound than passive appreciation. In 1995, Linda’s husband Jim shared with her an article in their local Allentown, Pennsylvania, newspaper discussing Steven Spielberg’s mission to collect testimony of Holocaust survivors and witnesses. Linda immediately knew that she wanted to participate.

In 1964, America’s first Holocaust memorial was unveiled in central Philadelphia at the head of Benjamin Franklin Parkway. More than 50 years later, the location surrounding this historically significant monument houses an interactive plaza, the Philadelphia Holocaust Memorial Plaza, a living monument to the 6 million lives lost in the Holocaust. The new plaza opened in October 2018 with onsite installations to inspire visitors to remember and reflect.

Twenty-five years ago, the world watched as the small African country of Rwanda descended into genocidal violence. Over the course of just a few months, forces in the government, media, military and general population attacked members of the country’s Tutsi minority, killing more than 800,000 of them in an organized campaign of genocide. In the years since, as the country has rebuilt and invested in a process of investigation, justice and reconciliation, the voices of survivors have become central.

Aliza Liberman’s upbringing in Panama is inextricably tied to the Holocaust: it’s where her Polish-Jewish grandfather, a survivor, immigrated to after World War II. This deep connection to the Holocaust is the main reason Liberman chose to support the Institute’s Dimensions in Testimony (DiT) program, which enables people to engage with a prerecorded video image of a genocide survivor by asking him or her questions and hearing the survivor’s answers in real time.