The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: A tribute

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (public domain photo)

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (public domain photo)Nobody came.

Soon after, a group of about 750 Jews, who had been stockpiling weapons, opened fire on the Germans, igniting the month-long Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

The brave resistance in the face of impossible odds has belied the myth – long ago debunked – that Jews were passive victims to the Nazi killing machine during the Holocaust.

To honor those who stood up to their Nazi tormentors beginning April 19 of 1943, USC Shoah Foundation is profiling Sol Liber, who – until his death last month at age 94 – was among the last living members of the Jewish resistance that fought in the uprising.

The insurrection ended on May 16, after Germans burned down the ghetto building-by-building, killing thousands of Jews in retaliation for a few dozen German deaths.

Owing to the chaotic nature of the battle, the official number of living survivors isn’t known. But five years ago, during a ceremony at the site marking the 70th anniversary, officials in Warsaw put the number at four.

Liber was the among the first Holocaust survivors whose testimonies were recorded by USC Shoah Foundation; specifically, he was the 58th interviewee of an archive that now contains 55,000.

Liber’s son, Rod, made arrangements for the 1994 interview. Then a studio executive, Rod spotted an ad in Variety Magazine from Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah – now USC Shoah Foundation – seeking Holocaust survivors willing to share their stories of survival on camera.

“I was already in the process of video-taping my dad’s story,” said Rod in a phone interview with the Institute last week. “I was excited at the prospect. They’ll do it more professionally than I ever could, and a few months later, we were taping the interview in my parent’s home.”

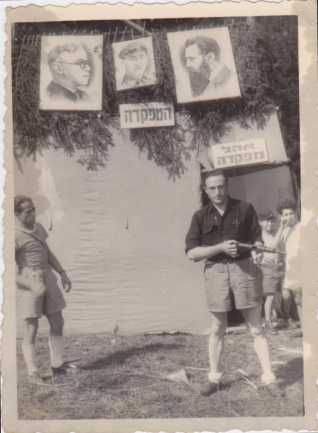

Sol Liber at a secret Hagganah training facility in Marseilles, France. 1948. Courtesy Liber family

Sol Liber at a secret Hagganah training facility in Marseilles, France. 1948. Courtesy Liber familyRod says his father didn’t mind talking about the uprising with family members, but he wasn’t nuts about recounting his story in front of large audiences.

“My dad was somewhat of a shy guy – not a public speaker,” said Rod, who grew up in Los Angeles and attended USC. “He had a fifth- grade education. … He was a smart man, but street smart, not school smart.”

Conscripted to fight for the Poles at age 15 during the onset of World War II, Sol returned to his home in the Polish town of Grojec after Poland’s surrender in 1939. Soon after, German occupiers forcibly relocated Sol, his parents and four siblings to the Warsaw Ghetto.

All Jewish ghettos were inhumane, but the Warsaw Ghetto was particularly heinous. Beginning in the fall of 1940, German occupiers had crammed hundreds of thousands of Jews into a mile-by-mile space. The streets were littered with the corpses of people who’d starved to death or were murdered by German gunfire. Germans sent Jews on trains from the ghetto by the thousand to the Treblinka death camp. Over a period of just six weeks in 1942, the population plummeted from 360,000 to 60,000.

Among the multitudes sent to perish at Treblinka were Sol Liber’s two teenage sisters.

Sol watched many of the packed trains leave the depot from a window of a forced-labor factory across the street, where he worked as a tailor repairing bullet holes in German uniforms.

Sol and his siblings often went to his uncle and aunt’s apartment in the ghetto. One day, the doorbell rang, and the uncle answered to see three or four members of the Jewish underground.

“They were asking for some money to buy weapons,” Sol said in his testimony, adding that his uncle was considered a rich man by ghetto standards.

When his uncle refused, they took a hostage – one of Sol’s cousins. After two weeks, the uncle relented and gave the group money. Not long after, Sol saw one of the men in the street.

“I say (to the man) what this all about?” Sol said in his testimony. “He says, ‘We have an underground. We're going to fight the Germans. I know we're not going to win, but we're not going to go (to the death camps) anymore.’”

In his telling, Sol joined the resistance. Among his tasks was to escort Jewish children through the sewers to rescue groups waiting outside. He said he also stored gasoline to make Molotov cocktails.

On April 19, the Germans and auxiliary troops came to liquidate the ghetto. When nobody heeded their loudspeaker call for Jews to empty out into the street, Sol said, the Germans left.

“Next day, they marched in, and we opened fire,” Sol said in his testimony. “And when we opened fire, a few fell, and they backed up. They backed out of the ghetto.”

The Germans reentered the following day in tanks. From rooftops, Sol and others hurled Molotov cocktails at them.

“Two tanks blew up, and the Germans escaped through the hatch,” he said.

By now, the battle was in full throttle. Later that night, Sol and four others ventured out of a bunker and headed for a factory that made airplane parts for the axis powers. To avoid detection, they walked in stocking feet, stepping over broken glass on the pavement. Upon arrival they heaved Molotov cocktails through the windows; the factory burned to the ground.

Amid the fighting – which raged mostly at night – Sol and others continued to smuggle children through the sewers to safety. Sol has said that one night, as he and a small group of kids and resistance fighters approached the manhole, they were met not by rescuers, but Germans. The soldiers opened fire; Sol took a bullet in the shoulder.

Germans rounded up the group and marched them to the train depot. They were transported to Treblinka. Shortly after, Sol and others were rerouted to the Majdanek camp in Poland to perform heavy labor. To avoid being deemed unfit and killed on the spot, Sol – with the help of a sympathetic doctor -- managed to conceal his wound.

After several months at Majdanek, where he was whipped and tortured, Sol experienced a period of chaotic movement. He wound up at Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, where he worked in the nearby salt mines. In May of 1945, as the Russians closed in – Sol and others were forced on a death march through German fields. He was liberated in June.

Sol spent three years at a displaced persons camp in Germany, another year in France, and resettled in Montreal, where he met a woman named Bella Bezonsky. They married in 1953. He worked as a tailor – specializing in women’s clothes -- and they had a son, Sheldon, and daughter, Susan.

Sol didn’t like the Canadian weather; the snow was a constant reminder of his wartime trauma. He had an uncle in California who spoke of sunny skies and unlimited opportunity. In 1957, Sol, Bella and their two infants got on a plane and flew to California. Here came another reminder of mortality: the landing gear on the plane was faulty and the pilots ordered the passengers to hunker into crash positions.

California lived up to the hype. After working as a tailor – for a time at a shop in Beverly Hills whose customers included celebrities like Doris Day -- he bought his own factory in downtown Los Angeles called S&D Fashions. In 1963 Sol and Bella had a third child – Rod. Sol sold the company in 1980, bought the building, and began a second career in real estate.

Sol died on March 21. At his funeral, Rod gave a eulogy that ended with a story.

When Rod was a boy, he used to ride with his father to deliver the raw material and patterns to men and women who worked from home. One day, their station wagon was violently broadsided by a car that ran a red light.

“Our car spun around on two wheels for a moment, witnesses would tell us later, but I’ll never forget my dad saying to me in the car, holding my little hand, ‘Don’t be scared. Don’t be scared,’” Rod said.

“In his final days, I don’t know if he heard me, but I said the very same thing to him. ‘Don’t be scared, Dad. Don’t be scared.’”