Bringing Stories to Daylight

With nearly 52,000 interviews from survivors of the Holocaust and other genocides, the archive of audio-visual testimony assembled and maintained by USC Shoah Foundation is so abundant it would take at least 12 years to watch it from beginning to end.

And that’s assuming the footage would be rolling 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

When I started my new job here at the Institute, I was struck by this statistic, which adequately conveys the scope of this incredible resource.

But it wasn’t until my colleagues in the communications department put it another way that the Visual History Archive’s profound potential as a tool for teaching and research really hit me.

So vast is this trove of testimony that anytime you select a segment at random, there is a chance it hasn’t been viewed in years. And there is an even better chance the testimony has never been written about or incorporated into a classroom project.

Analytic reports by the Institute show that a little more than a quarter of all the testimonies in the archive were viewed in some capacity last year.

This means the very act of using the Visual History Archive for research purposes is not only educational, it’s adding to the bank of knowledge on world history, however small.

I think it is this potential for discovery that makes primary sources such an exciting tool for teaching and research. It helps explain the popularity of the Institute’s educational resources, such as IWitness.

The Visual History Archive has led to some significant academic discoveries – such as the existence of certain labor camps, or the long-term migration patterns of refugees. But it also inspires discovery on a more intimate level: To listen to an interview is to give voice to the story of one person touched by history.

I watched just a few minutes of Abram Goldszer’s three-hour testimony, taken in 1998 when he was 67. During this short viewing, I was spellbound by the wrenching vividness of his recollections.

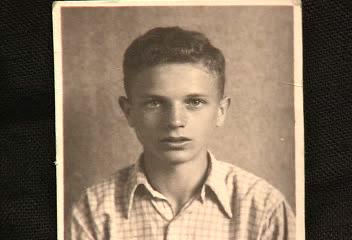

Abram Goldszer in 1945 he was 15 years old.

Abram Goldszer in 1945 he was 15 years old. All the while, Goldszer witnessed horror at every turn: The point-blank execution of a close family friend standing next to him, an outbreak of typhoid fever that killed hundreds around him at a death camp, the devastating separation from his parents – first his father, whom he saw led into a truck that trundled away, then his mother, who was led into a cattle car headed for a death camp.

I searched for Goldszer’s story online, and came up with no mention of his account as a survivor. As far as I know, nobody has relayed any segment of his amazing three-hour testimony.

I think his story illustrates how danger lurked around every corner for European Jews during World War II. Survival was a function of luck, grit and the whims of the Germans. Like a Civil War letter stashed away in an attic, Goldszer’s story has been patiently awaiting discovery.

The Institute has spent years and years gathering, indexing and preserving these 107,000 hours of testimony. Now it is incumbent upon us – as teachers, as researchers, as an Institute, as any person with even a passing interest in human rights and decency – to help bring these stories to daylight.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.