What is the Story? Two Sonderkommando Interviews in the USC Shoah Foundation Archive

By Dawn Skorczewski

Stulberg: Were you ever in the gas chamber? Did you see the gas chamber?

Venezia: Of course I was every day over there.

Stulberg: Can you describe to us what it looked like?

Venezia: It’s nothing to describe It was an empty room. You could imagine for three thousand people to go in there. I can tell you that. As soon as the transport train was coming, like I told you, my mother was in lines with the kids and the pregnant women, and so on.

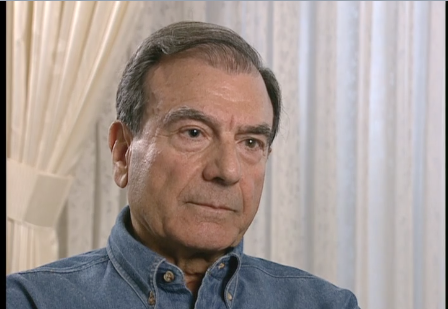

Morris Venezia

Morris VeneziaThe USCSF interviews are not documentary films, nor are the interviewers filmmakers. As volunteers, they received several days of training before they conducted an interview. At first glance, they appear to have no agenda other than asking the questions provided on the interview questionnaire. But the act of interviewing and the nature of the subject combine to make it a highly intersubjective process. Choosing interviews of Greek survivors who speak in English for several segments on the tape about the Sonderkommando work detail, I watched the interviews in their entirety, but viewed the sections about the gas chamber detail many times. Sometimes, the survivor seems to challenge the interviewer’s questioning style or the USCSF questionnaire itself. At other times, the interviewer guides the survivor’s narrative in directions which conflict with what the survivor seems to want to say.

Venezia’s cousin Dario Gabbai, born September 2, 1922 in Salonika, Greece, tells his story to Yitzchak Kerem on October 9, 1994 in Los Angeles, CA. When they begin to discuss Gabbai’s work in the gas chamber, Kerem asks a series of pointed questions:

Kerem: So, when they would open the doors to the gas chamber, whose job was it to take the bodies out?

Gabbai: They’d give us some canes. You reverse the cane and drag ‘em out. Because when the gas, they’d get very tight and it takes a lot of force to be able to drag the bodies from the gas chambers to put it in the elevator going to the second floor. But there were enough people there to do it.

Kerem: How many people, would you say, were working in each crematorium?

Gabbai: Uh, we were about 100 I think. 1,200 people all together in the Sonderkommando. But we were 100 in mine, 100-150. The others were around for other things. We had enough personnel. But you know, we were working shifts also.

Kerem: How many of you were Greek?

Gabbai: Uh, we were 35 Greeks, and at the end we left only 26.

Kerem: So after taking the bodies out of the gas chamber and putting them on these elevators, then what would happen?

Gabbai: We’d put them in the ovens.

Kerem: Who would put them in the ovens?

Gabbai: Our group. In stretchers. Actually, outside the women and inside the men because the women had more fat and could burn better.

Kerem: How many people were, uh, you able to actually put inside of each oven?

Gabbai: We put about four.

Kerem: And how many ovens were there working all the time?

Gabbai: In each crematorium there were about eight ovens.

Kerem: And, uh, how long again would it take to burn–

Gabbai: 20 to 30 minutes.

Kerem: After the process was over, the actual burning, then what would you do?

Gabbai: Oh then, ya know, take the ashes out and pulverize the ashes and trucks come take it.

Dario Gabbai

Dario GabbaiLet’s return to my epigraph, in which Venezia speaks about the same subject. After saying “there is nothing to describe,” he offers a long descriptive narrative. He does not answer the question. Venezia draws a scene for his listener, who remains silent. He is dramatic. His voice changes tone. He speaks quietly, then loudly. He pauses, as if to gather strength. He does not offer a word about the physical detail of the gas chamber. Indeed, he suggests that that is not where the story lies. His story is about people: what they looked like, what their ages were, how they moved, and how they sounded. It is also about his own response. He had to run away as best he could. He registered shock and disbelief.

Venezia does not leave space for the kinds of questions that Gabbai answers so meticulously. He goes on:

And the women, of course, they were ashamed to be naked, like this. They would go one room to another so close! And the kids! [Pause] Near to the mother as you know. And everybody’s screaming and so on and so on. And they were going right… in the gas chamber. In the meantime, in the back from another room come naked the men. And when the women would see the men naked they would start, again… screaming! [Imitating] It’s a shame! It’s a shame! It’s a shame! … So, when they was the men here and the women screaming, the German, with a ….

Stulberg: With a cane? A stick?

Venezia: With a cane… hitting the mens on the head… and the men they were going to get away and they were going with the women together. And when everyone was in, close the door.

[Pause]

V: In the beginning [pause]… I was there. After they close the door I could hear the three thousand people, voices, cry and screaming...And you could hear [sings] Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu[1]…[Pause] they were calling God! Nothing happened, Never nothing happened and these voices still in my ears. But, other transports was coming, I was hiding again. I was getting TOO FAR AWAY not to hear those voices calling God. I never went back again. But! If a soldier or German or SS was finding me hiding he could shoot. But! I could not stand those voices. [Pause]

Notice how dramatic this story is, filled with song and image. Venezia tells it from the sidelines, asking his listeners to stand with him to see and hear what he saw. Entering the experience from this perspective, I cried when I heard it for the first time. Sometimes I cry again when I show it to students or a colleagues.

Dario Gabbai lights a memorial candle at Auschwitz on Jan. 27, 2015

Dario Gabbai lights a memorial candle at Auschwitz on Jan. 27, 2015It might be tempting at this point to privilege one of these interviews over the other, or to say that one survivor is more accurate or his story more true. But the value of the thousands of testimonies in the USCSF collection lies in the simple reality of its numbers and the availability of access. To achieve an understanding of the gas chambers at Auschwitz, I urge my students to begin by watching several survivors speaking about the Sonderkommando detail, and to carefully track their viewing experiences. What facts do they learn from each? What else do they glean from the experience? In writing about these two –the “what” of the facts and the “how” of how these facts are conveyed—students learn to recognize the many ways in which knowledge about the Holocaust is conveyed. What is “true” becomes less important than what they can learn about how the many and sometimes competing versions of the truths are told.

Works Cited

Dawn Skorczewski is Director of University Writing and Professor of English at Brandeis University. She is the author of Teaching One Moment at a Time: Disruption and Repair in the Classroom (U Mass 2005), An Accident of Hope: The Therapy Tapes of Anne Sexton (Routledge 2012), and co-editor of The Happiness Reader (Macmillan 2016). She is working on Dutch Memory Matters,a book about Dutch testimonies in the USC Shoah Foundation archive with Bettine Siertsema, Professor of History at VU Amsterdam.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.