Holocaust Survivor Zenon Neumark Speaks to Students and Donates Historical Documents

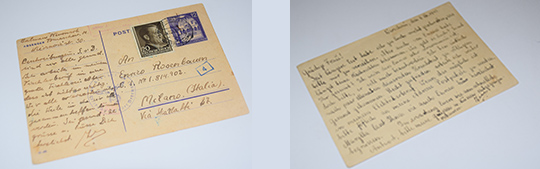

Postcards written by Zenon Neumark during World War II, donated to USC Shoah Foundation

On a recent Thursday afternoon, Holocaust survivor Zenon Neumark spoke at USC Shoah Foundation about his experience as a Jewish resistor who avoided the death camps by escaping from the Nazis multiple times, emphasizing how lucky he was and how many people helped him.

“Nothing was easy, everything was risky, but I was lucky,” Neumark said. “And I always thought every morning, ‘What can I do today to better myself?’”

While he was at the Institute, Neumark also presented Professor Wolf Gruner, director of the Center for Advanced Genocide Research, with a donation for USC Shoah Foundation: two postcards he had written to his uncle in Italy while he was evading the Nazis. He plans to donate more remnants of his time during the Holocaust to USC Shoah Foundation, and Gruner will be starting a special collection for him through the USC Libraries.

Gruner asked Neumark to speak in particular for his HIST 446: Resistance to Genocide class, though the event was open for students and interns at the Institute to attend.

Neumark started the talk by telling attendees the story of his survival. At the age of 16, he managed to escape the Jewish ghetto in his Polish hometown simply by jumping the fence of their work site at an opportune moment.

“The Germans were so organized and so efficient and so disciplined that they didn’t expect anyone to escape,” he said. “Actually, not many escaped.”

Zenon Neumark

Zenon Neumark“The problem was when you joined an underground the number one promise you made was that you would keep it a secret… When the third one came in, that was really a problem,” Neumark joked. “I couldn’t tell them I was already in two.”

While in underground organizations, Neumark aided friends, who would not have been able to survive on their own, by getting them sent to a different branch of the company where he worked while in Warsaw.

“One day I got a letter from one of them, he says, ‘Zenon, don’t send any more, we are in the majority,’” he said. “Of 25 [workers] 13 were Jews.”

His activity in resistance movements ended in 1944, when the Warsaw Uprising took place. Neumark was arrested simply for being a young Pole and managed to get himself sent to Vienna, where he had always wanted to visit and thought he could find “fellow” Catholics who might sympathize with him. In Vienna, Neumark was in a work camp, but escaped, later re-entering the camp, where no one had noticed he was missing, and then leaving again.

Neumark left the second time because he had found work for a Nazi businessman who was interested in him because he believed him to be an electrician.

“I didn’t know the first thing about being an electrician,” Neumark said. “But, he had electricians from many other countries, and the fact that I could speak German and knew some Slovak, Czech, Armenian, helped me to help him translate.”

Since no one knew Neumark was Jewish, he managed to live a civilian life in Vienna, working regularly, living in an apartment and traveling around Vienna freely until the war ended.

After the war, Neumark decided to pursue his newfound field by studying electrical engineering at the University of Milan.He later came to the United States, first to Oklahoma and then to Los Angeles where he worked at the Hughes Aircraft Company.

In 2006, Neumark published his memoirs, Hiding in the Open: A Young Fugitive in Nazi-Occupied Poland.

“After I retired I had more time,” he said. “So I got to read some of what my friends [who were fellow survivors] wrote. And I just noticed that my story is quite different and could be more interesting. My day was not like the day before or the next day.”

One thing Neumark said was different about his experience was because he was on the outside, he was able to realize how many good citizens there were who were willing to help Jews in need. Neumark said that because many Jews were killed anyway, and others could no longer remember the names of those who came to their aid or never knew them, thousands of resistors will never be recognized.

“One thing that [those in camps] never knew was how many good people there were who helped me,” he said.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.