USC literature professor receives USC Shoah Foundation grant for innovative use of poetry by genocide survivors

EDITOR’S NOTE: USC Shoah Foundation this year launched an initiative to give out small grants to USC professors of any discipline who incorporate the Institute’s archive of genocide-survivor testimony into their coursework in a way that emphasizes diversity and inclusion. This is the third story in a series of five about the 2017 recipients.

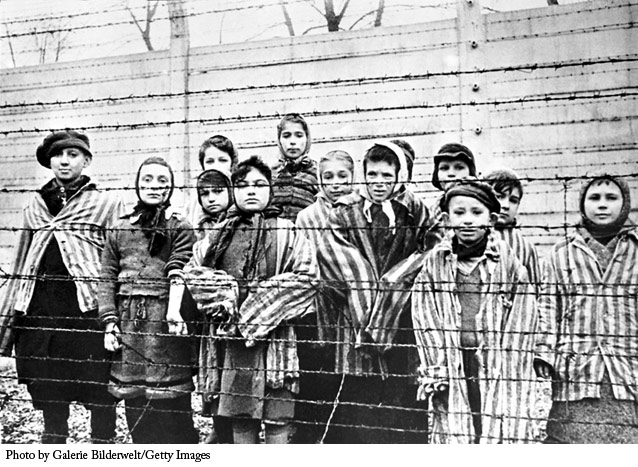

Eva Slonim (the girl wearing the head scarf) composed a poem along with a group of other children while imprisoned in Auschwitz.

Eva Slonim (the girl wearing the head scarf) composed a poem along with a group of other children while imprisoned in Auschwitz. “Just like a leaf tossed to the wind,

Separated from its branches and tree,

Not belonging anymore—

Liberated, but not free.”

This is opening stanza of a poem by Holocaust survivor Itka Zygmuntowicz, who read “A World That Vanished” on camera in her testimony with USC Shoah Foundation.

It is among several poems read by the genocide survivors who authored them during the recording of their testimonies for the Visual History Archive that Dr. Beatrice Sanford Russell, an English literature professor at USC, assigned to her students last semester in her “Poetry and Protest” class.

For her innovative use of testimony, Sanford Russell was a recipient of USC Shoah Foundation’s Diversity and Inclusion Through Testimony (DITT) grant.

Sanford Russell had taught Holocaust literature before, and had worked with audiovisual material. But she didn’t begin weaving genocide-survivor testimonies into her syllabus until this year, in response to USC Shoah Foundation’s call for grant applicants.

“The inclusion of testimonies had a drastic impact on the way that the course’s messages came across to the students,” she said. “There was a heightened sense of stakes within the classroom discussion, because these poems were tied to people who felt very real to the students, because they had seen their faces and heard their voices and distinctive stories of survival.”

Students in Sanford Russell’s class read several poems by Holocaust survivors and wrote essays defending the use of poetry as a form of testimony in response to German philosopher Theodor Adorno’s famous claim that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.”

Included within the course’s syllabus is the testimony of Holocaust survivor Eva Slonim, who was depicted in an iconic photo of a group of children standing behind the barbed wire at Auschwitz after liberation in 1945. Slonim is also the author of many poems, in which she details her life as a prisoner of Auschwitz.

She composed one poem along with a group of other children while imprisoned in Auschwitz. It reads:

“The camp is as large as the whole world to us,

And it’s full of barracks.

Be happy and rejoice, handsome Jewish worker!

Soon this nightmare will come to an end.

The great day of change is approaching,

And the Jewish suffering will forever end.

We will return to our nice homes,

Embrace our beloved parents, and all loved ones that we haven’t seen for so long.

There will be table full of plenty, beautiful clothes, toys,

And nothing will ever go wrong.”

A student in the class observed: "The description of the camp being ‘large as the whole world’ immediately instills both the feeling of being a child and the feeling of having a limited access to the world, both of which are crucial to understanding Eva’s perspective as a survivor.”

The student added: “Rather than flushing away details from history, poetry can add infinitely more if you read between the lines, and in this case those details can be the key to readers empathizing with her and other victims of the Holocaust.”

Beatrice Sanford Russell

Beatrice Sanford RussellAnd after watching the testimonies in class, “the classroom seemed quieter and more serious, but the students were totally engaged,” she said. “There was a sense that we all were processing together what we had seen, and it really felt like a collective emotional experience.”

Sanford Russell, who is working on a book manuscript titled Romanticism and Repetition, 1790–1870, said she plans to continue using the audiovisual testimonies when teaching the course in coming semesters.

“Speaking personally, I found them very moving,” she said. “From an instructional perspective, the testimonies challenged me to continue to bring additional media perspectives to my other courses.”

The 2018-19 Diversity and Inclusion Through Testimony Grant Call for Proposals will be published in August. Please check back here for more information.

A photographer from the Red Soviet Army unit that had liberated the Auschwitz extermination camp on January 27, 1945, took this photograph of child survivors a few weeks later.

Click on any of the children's faces in the photo to learn more about what has happened to them since this photograph was taken.

These are some of the children who survived Auschwitz

The iconic image, taken by Alexander Vorontsov, a cameraman attached to the 1st Ukrainian Front, who liberated the camp in the winter of 1945, shows 13 grim-faced children in prison garb gazing at the camera opposite the barbed wire. Eight of the 13 children are still alive today. Click on each of the children to learn more about them.

Tomi Shaham

Tomi Shaham was just 11 years old when he entered Auschwitz, but he took on the responsibility of looking after younger children in addition to helping his family and keeping himself alive for almost three months until liberation.

Tomi was born on July 1, 1933, and lived with his parents and two brothers in Nitra, Slovakia. Though his family tried to cross the border into Hungary in 1941, they were not able to escape and were sent to the Sered camp in Slovakia in October 1944. One of Tomi’s brothers escaped the camp and made it into Hungary, but Tomi later found out that he had died in the Budapest ghetto. On Nov. 3, 1944, Tomi, his remaining brother and their parents were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Because it was so late in the war, the Nazis were no longer making selections upon arrival at Auschwitz. Tomi and his family spent two days in the “family camp” section of Birkenau before the men and boys over age 10 were separated from the women and children. Tomi was 11, but his parents told him to say he was nine so he could stay with his mother and the rest of the children. After two more days, Tomi’s mother was sent away and Tomi found himself one of the oldest in the children’s block.

For the rest of his time in Birkenau, Tomi helped others. He put himself in charge of 10 children but despite his care, nine of them died of dysentery. The one boy who survived would later remember Tomi hitting him to coax him to eat so he wouldn’t die. Tomi also periodically met his father and brother through a fence. They would throw him cigarettes they got from the Red Cross so he could trade them for bread from the dysentery and typhus patients. He would then distribute it among his father and brother and the children he looked after.

As the Soviet army drew closer, the Germans at Birkenau disappeared for a week, during which time Tomi and the other children raided the storehouses for clothes and food. The rest of the adults were sent out on what would be death marches to lands that were still under German control, where Tomi’s father died, and later the children were taken on a march back to Auschwitz. But before Tomi and the others had reached Auschwitz, the Germans marching them got in a truck and drove away. The children continued on to Auschwitz anyway, and the Soviet Army liberated them on Jan. 27, 1945.

Tomi quickly befriended the Soviet soldiers and took them on a tour around Auschwitz, pointing out what each building was for. He spent so much time with them that one soldier even wanted to adopt him. After three months recuperating in Auschwitz, Tomi went to Budapest to find his uncle and learned that his mother had survived.

Tomi immigrated to Israel in March 1945, where he became a teacher – inspired, he believes, by his experiences helping the children in Auschwitz. He married and had three children and four grandchildren, and still speaks to young people about the Holocaust.

Erika Dohan Winter

Erika Winter Dohan and her family received help from many Gentiles in the first years of the Holocaust, but eventually they, too, ended up at Auschwitz.

The Winter family owned a movie theater in their town of Trnava, Czechoslovakia. Erika, born March 3, 1931, had one younger brother, Otto. She remembers that Jews in the town began losing their businesses when anti-Jewish laws took effect in the late 1930s, but her family was able to keep the movie theater until 1939 or 1940 because it was deemed important for the local economy. However, once the theater was ultimately taken away, her father had to find new work as an accountant.

Erika’s father was friendly with many police officers in the town through his work, and one day, an officer warned him that Jews would be deported that night. Her parents took Erika and Otto to a farm at the end of their street to hide. They stayed for three days and then returned to their apartment. Later that week, police arrived at the house to arrest Erika’s father. They took him to a small collection camp with the rest of the Jewish men from the town, and Erika and her mother went to visit him once. The second time her mother went, he was gone. They never saw him again.

Erika, Otto and their mother joined her mother’s aunt in the home of a Christian family that had agreed to hide Jews for money. But after just over a week, others in the town discovered them and informed the police. Erika and her family were taken first to the Sered concentration camp and from there, to Auschwitz. It was November 1, 1944.

Once they arrived, Erika and the others on the transport were taken to a family camp barrack and allowed to keep their clothes, food and belongings, much to the astonishment of the other inmates. However, this would not last – the women were separated from the children and taken to a camp in Germany after a few days. The night before the women left, Erika’s mother snuck into the children’s barrack to say good bye to Erika and Otto and tell them where to meet up with the family after the war was over.

Once they were on their own, the children lived in the “gypsy” camp, a harsh place with little food. Across from their barrack was a barrack that housed elderly people and women with babies, and there Erika found her great aunt. The people in this barrack got hot cereal, and this great aunt traded her own bread to get cereal for Erika and Otto. But after a while, she disappeared.

In January, as the Soviet Army drew closer, the Germans began evacuating the majority of the camp on death marches to lands that were still under German control. Erika remembers one day the entire camp was forced to stand outside in the snow for hours. She and a friend snuck back into the barrack for a few minutes to get warm, and when they went back out, everyone was gone, most likely to their death on the march. Only a few children and the sick were left. The Red Army liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau on Jan. 27, 1945.

Erika and Otto recuperated in a convent in Katowice, Poland, and later a displaced persons camp until they made their way back to Trnava and reunited with their mother and other family members. Erika met her future husband Karol Dohan in a Jewish community youth group and moved to Israel with him in 1949. They both served in the Israeli Army and were married in 1951. Erika and Karol (who died in 1985) have one son, Ariel, and three grandchildren.

Marta Wise

Marta Wise says it was nothing but “pure, unadulterated luck” that allowed her to survive the Holocaust.

Born in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, on Oct. 8, 1934, Marta lived happily with her brother, four sisters and parents, who owned textile mills and shops and maintained a very religious household. Once Germans occupied their country, however, Marta’s father sent each of the children out of Czechoslovakia with false papers; a German woman named Mrs. Tafon passed Marta off as her daughter and took her to a distant cousin of Marta’s in Hungary, where Marta lived for two years.

In 1944, Germany invaded Hungary and conditions became just as dangerous as in Czechoslovakia. Marta’s father quickly sent Mrs. Tafon to take Marta to Budapest to begin the journey back to Czechoslovakia. In Budapest, Marta’s aunt gave her an agonizing choice: sail with a group of children to Palestine or return home to her parents. Marta, still only nine years old, chose home. The boat to Palestine sank, killing every child on board.

After a harrowing two-day trek through wheat fields over the border, Marta joined her younger sister Eva in Czechoslovakia for two months pretending to be Catholic. The sisters were arrested on Marta’s 10th birthday, interrogated and beaten for a week but they refused to admit they were Jewish. Eventually, the family’s former nanny was questioned and she immediately betrayed them. Marta and Eva were sent to the Séréd transit camp and from there to Auschwitz.

During the selection upon their arrival in Auschwitz, Eva was sent to the right and Marta to the left, which meant her immediate death in the gas chambers. But at that moment, Soviet planes flew overhead and the two lines were pushed back together in the subsequent confusion. Marta was saved, and the two were sent to the “family camp” section of Auschwitz. There, Dr. Josef Mengele gave them mysterious injections (Marta has never known what they were for) and they spent their days trying simply to survive.

In January 1945, the approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on what would be death marches to lands that were still under German control, but Eva and Marta stayed behind, and the Red Army liberated them on January 27, 1945. After a few months of recuperation, they hitchhiked their way back to the old family home in Bratislava, where they were reunited with their parents and all their siblings except their little sister Judith, who they found out had died in Auschwitz. But not long after, their older brother Kurti drowned, and the family left Czechoslovakia for Australia in 1948.

Marta finished school, studied physiotherapy and in 1967 married Englishman Harold Wise. In 1998, they moved to Israel. They have three daughters, Judy, Michelle and Miriam, and 14 grandchildren.

Eva Slonim

Though they came from the same family, Eva Weiss Slonim and her sister Marta (standing next to each other in the photograph) each had to overcome different challenges to survive the Holocaust.

Eva was born August 29, 1931, the oldest girl among six siblings in her family when World War II began. Though she had had a happy childhood, Germans invaded her hometown of Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, in 1939, and began confiscating Jews’ belongings. Their non-Jewish friends stopped talking to them and Eva remembers German soldiers viciously attacking her grandfather in their home, which was her first sign that the situation was very serious.

Eva’s father, a textile manufacturer and shop owner, employed a beautiful German woman named Mrs. Tafon to take each of the children to relatives’ homes in Hungary on false papers. Only Eva –who with light hair and blue eyes had a greater chance of passing as Gentile – stayed in Bratislava with their parents. Eva would often place dolls in a baby carriage and take them to pick up their food rations so neighbors wouldn’t suspect that the rest of the children were gone.

After about two years, conditions in Hungary became so bad that Marta and the other children attempted to return to Czechoslovakia. Eva and Marta posed as Catholic orphans in a flat in Nitra, Czechoslovakia, for several months, until soldiers interrogated and arrested them. Even Eva’s new friend, a girl her age whose father was a top SS officer, could not save them from being sent to Séréd concentration camp and then to Auschwitz.

Because they were sisters but had different-colored eyes and hair, Eva suspects, she and Marta was sent to Dr. Josef Mengele’s infamous barrack which housed twins and people with physical abnormalities who were to be subjected to his medical experiments. Eva was given injections that gave her stomach cramps, had large amounts of blood drawn, and was forced to play games with the other children in which they inadvertently chose Mengele’s next victims. A sign reading “Each beginning has an end” hung in the barrack.

Eva contracted dysentery and typhoid but Marta stole potatoes for her which saved her life. In January 1945, the approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on what would be death marches to lands that were still under German control, but Eva and Marta stayed behind, and the Red Army liberated them on January 27, 1945. After a long journey back to Bratislava, Eva and Marta were reunited with their parents and siblings except for one sister who had been killed.

The family immigrated to Australia in 1948 after Eva’s brother died in a drowning accident. Eva worked long days in her father’s new wafer factory and went to school at night. She met her future husband, Benjamin Slonim, at her 17th birthday party. After they were married in 1953, Eva worked as a bookkeeper and secretary and they had five children, Edwin, Malcolm, Sharona, Daniel and Aviva. Eva and Benjamin have 24 grandchildren.

Eva Mozes Kor

Even in a tiny farming village in Romania, the Holocaust found Eva Mozes Kor. Eva, born Jan. 31, 1934, was brought up in a very religious household with two older sisters and her twin sister, Miriam. The Mozes family lived and worked on their large farm in Portz, and they enjoyed a life full of the warmth of family. However, when Hungary annexed the slice of Romania where the Mozes family lived, they faced intense anti-Semitic harassment from students and neighbors. Classmates who were once friends now spit on Eva and called her names. Taunting youth often surrounded the Mozes’ house and threw food and rocks at it for hours. They were the only Jewish family in the village.

Eva and her family were forced to move into the Cehei ghetto in Simleu Silvaniei, Romania, in 1944, where they stayed for about two and a half months. The ghetto had no housing facilities, so the family made a tent out of sheets, which the Nazi commandant would order them to tear down and rebuild in the rain to torment them. In May, they were squeezed onto cattle cars with the rest of the ghetto and sent to Auschwitz. Eva remembers her father saying his morning prayers even as they arrived at the camp.

On the selection platform, Eva and Miriam were immediately recognized as twins and separated from the rest of their family, who was taken to the gas chambers. They were taken with other twins to a special barrack, where Dr. Josef Mengele housed subjects for his medical experiments. When Eva came upon the corpses of three children in the latrine on her first night in Auschwitz, she made a silent pledge to do everything in her power to make sure she and Miriam would not end up on that filthy floor.

Mengele gave the twins injections, drew large amounts of blood, and meticulously measured their body parts and photographed them, often for six to eight hours at a time. One injection left Eva gravely ill. She was separated from Miriam and left to die in the sick ward. She remembers Mengele saying sarcastically, “Too bad, she’s so young—she has only two weeks to live.” Determined to prove Mengele wrong, Eva battled the high fever and five weeks later was reunited with her sister.

That winter, the approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on death marches to lands that were still under German control. The Soviet Army reached the camp on Jan. 27, 1945, where only the children, elderly, and sick were left behind. Eva and Miriam were first sent to a convent in Katowice, Poland, to recover, and from there traveled with other survivors to Minsk, in the Soviet Union. A woman named Mrs. Csengeri, who had been imprisoned In Auschwitz and was a friend of Eva’s mother and the mother of twins herself, took care of Eva and Miriam until they made it back to Romania and were reunited with an aunt and a cousin. In 1950, Eva and Miriam moved to Israel. Eva served in the Israeli Army for eight years.

Eva married Holocaust survivor Michael Kor in 1960 and joined him in Indiana and had two children, Alexander and Rina. She dedicated herself to raising awareness about Mengele’s Auschwitz medical experiments, and in 1984 she created Children of Auschwitz Nazi Deadly Lab Experiments Survivors (CANDLES) to unite the survivors and lobby for the release of Mengele’s files. In 1995 she founded the CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Terre Haute, Ind. That same year, Eva made a profound personal discovery: she had the right and power to forgive the Nazis, though she would never excuse their actions. By exercising this power, she says she freed herself of the burden she had carried for 50 years. Eva passed away at the age of 85 in 2019.

Gabriel Neumann

Though he is the youngest child in the photograph, Gabriel “Gabi” Neumann was not spared from the death and destruction of the Holocaust.

Gabi was born in Obyce, Czech Republic, on Feb. 25, 1937, and lived with his parents and older brother and sister. In 1944, the family was deported to the Novaky camp but was able to return to Obyce. The Sered camp opened in 1943, and Gabi’s parents found work for themselves in the nearby village Zamianska Kert, in a farm and a tobacco factory, so they and the children could avoid the camp. However, when the Germans came to take people to Sered, Gabi, his mother and siblings ran to the nearby forest and hid while his father found a different hiding place. Two months later, they were betrayed by people from the village and sent to Sered.

On Nov. 3, 1944, Gabi and his mother and siblings were sent by cattle car to Auschwitz on one of the last transports into the camp. Because the war was drawing to an end, the Nazis did not make selections for the gas chambers and sent Gabi and his family to the “family camp” section of Birkenau. After a week, Gabi, who was six years old, was left in the children’s block while his siblings and mother were sent elsewhere. Children would often disappear from their bunks for medical experiments, but Gabi believes he was saved because he slept near the back of the barrack instead of the entrance.

Except for a daily line-up and one meal a day, Gabi and the others did nothing except huddle by a small oven for warmth. His brother would sometimes visit him and pass sugar cubes through the electric fence that separated their barracks, or they would meet at the fence at night even though they could have been shot. Gabi realized that people who went to the hospital barrack could avoid the line-up, so he pretended to be sick for a time. His sister did fall ill, but joined him in the children’s block after she was released from the hospital.

In January 1945, the approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on what would be death marches to lands that were still under German control. Gabi and the other children marched from Birkenau to Auschwitz, and made it back even after the Germans who were marching them suddenly disappeared. The Red Army liberated Auschwitz on January 27, 1945.

Gabi says that his mother found him and his sister after liberation from the names of the children in the now-famous Soviet photograph from behind the barbed wire. His father had died on a march from Auschwitz to Gleiwitz. Gabi’s brother, Elhanan Neumann, survived the war and was liberated from Mauthausen concentration camp. Elhanan lives in Israel. Gabi immigrated to Israel on a Youth Aliyah program in 1949 and later married, had one son, and became an artist and graphic designer. He died in 2012.

Miriam Mozes Zeiger

Miriam Mozes Zeiger didn’t have long to enjoy her idyllic childhood on a farm in Portz, Romania. By the time she was ten years old, even school had become a place of torment and oppression.

Miriam lived with her twin sister Eva (both born Jan. 31, 1934), their two older sisters, and parents on a working farm in Portz, a rural village without running water or electricity. They were the only Jews in town and lived a very religious lifestyle. But when Miriam and Eva started school in 1940, the Hungarian occupation had just begun, and anti-Semitism was high. The girls were punished for a prank some boys played on their teacher because they were “dirty Jews” and were spit on and pushed around. Their teacher even showed a movie in class about how to catch and kill Jews.

Though the family tried once to escape Romania (they were caught at the border of their property and forced to return home), they were sent to the Cehei ghetto in Simleu Silvaniei, Romania, in 1944. They stayed there for about 2 ½ months while Nazis tortured their father, who they insisted was hiding gold and silver. All the inhabitants of the ghetto were put on cattle cars and told not to bring any belongings because where they were going, they would have everything they needed.

At Auschwitz, Miriam and Eva were separated from their family and put into Dr. Josef Mengele’s barrack for twins and others who would be subjected to his medical experiments. Miriam and Eva were separated for two weeks, and Miriam was under constant Nazi surveillance while Eva was given injections. Later, they found out that if Eva had died, Miriam would have been killed immediately, as well, so their autopsies could be compared. Over the next nine months, Miriam contracted dysentery and a kidney infection as a result of injections she was given. Yet the two survived.

The approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on death marches to lands that were still under German control. The Soviet Army reached the camp on Jan. 27, 1945, where only the children, elderly, and sick were left behind. Miriam and Eva recovered at a convent in Katowice, Poland, before making their way back to Romania under the care of Mrs. Csengeri, who had also been imprisoned In Auschwitz and was a friend of Eva’s mother and the mother of twins herself. Miriam and Eva reunited with an aunt and cousin before moving to Israel in 1950.

Miriam studied to be a nurse, married Yekutiel Zeiger, and had three children, Yaffa, Ariella, and Ayala. She also had ten grandchildren. However, she suffered from kidney disease all her life because of Mengele’s experiments. Eva donated a kidney to Miriam in 1987, but Miriam developed cancer and died June 6, 1993.

Ruth Muschkies Webber

As a five-year-old, Ruth Muschkies Webber didn’t always understand what was happening when World War II began and Germans invaded her hometown of Ostrowiec, Poland. But when she saw the fear in her parents’ and grandparents’ eyes, she knew something was terribly wrong.

Ruth, born June 28, 1935, lived with her mother and father, a photographer. Her maternal grandparents lived close by and her paternal grandmother lived with them. Her older sister Helen was a piano prodigy who studied in a conservatory in Warsaw. In 1939, Germans invaded the town and her father’s studio was taken away soon after. Ruth remembers coming home one day to find her parents and grandparents crying – her grandfather had had his beard shaved off in the street. By 1940 the Ostrowiec ghetto was formed and their home became part of it. Helen returned from Warsaw and she and Ruth had to spend the majority of time inside their home with their grandparents. Ruth’s father, Samuel, used his connections within the gentile community to find a home for Helen to live and continue her education posing as a Christian orphan for the duration of the war. Ruth was too young at the time to safely follow the same route.

Ruth’s parents secured places for themselves at the Bodzechów work camp and smuggled Ruth in, where they hoped they would all be safe. Her grandparents and other family could not go and were eventually sent to Treblinka, where they were killed. Ruth hid wherever she could since children were not allowed in the camp, and would often go with her mother to the forest to avoid being transported to an extermination camp. Though she lived in constant fear of being discovered and shot on the spot, Ruth daydreamed about what life might be like if she could run and play like other children.

After being moved to various other ghettos and concentration camps, Ruth and her mother (her father had already been separated from them) were sent to Auschwitz in August of 1944. While her mother was selected for work, Ruth often hid in a barrack that was filled with corpses – she even played there, Ruth remembers, so accustomed was she to death. Ruth became sick with measles and pneumonia, and later with tuberculosis, but through the help of other prisoners and by hiding her symptoms she avoided being selected for the gas chambers. In October 1944 Ruth’s mother was sent out of Auschwitz on a transport to another camp leaving Ruth devastated.

In January 1945, the approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on what would be death marches to lands that were still under German control. Ruth and other children, and the elderly and sick were left behind to be executed. The Red Army liberated them on January 27, 1945. Ruth and the other children were sent to an orphanage in Krakow to recover where her mother found her from a list of the children’s names posted at a train station. The two reunited with Helen and after 2 years in Munich Germany moved to Toronto in 1948 to live with distant relatives. Ruth’s father and 35 other immediate family members did not survive.

Ruth married fellow Holocaust survivor Mark Webber in 1956 and moved to his home in Detroit. They had three daughters, Shelly, Elaine and Susan, and five grandchildren. Ruth keeps in close touch with Miriam Friedman Ziegler and Paula Lebovics, who were also from Ostrowiec and are pictured in the photograph.

Shmuel Schelach

Shmuel Schelach (born Robert Schlesinger) was one of the very few who managed to survive the Holocaust with his immediate family intact, though when this photograph was taken he had just endured three months in Auschwitz alone with his little brother.

Born Jan. 19, 1934 in Mytna Nova Ves, Czechoslovakia, Shmuel lived with his mother, father – who managed agricultural farms – and brother Palo, who was four years younger. During the first wave of transports of Czech Jews to concentration camps in 1942, Shmuel’s family tried to cross the border into Hungary, but did not succeed. Since they could not go back home, they rented an apartment in Nitra, Czechoslovakia, and Shmuel’s father began working in a brick factory. The manager of the factory was not a Jew, but he offered to hide the family in the factory in exchange for money.

On September 5, 1944, the family received orders to report to Gestapo headquarters. Early that morning, Shmuel’s mother dressed Shmuel and Palo in warm clothes and instructed them to go ahead to the factory alone – the parents would follow later so as not to arouse suspicion. Shmuel and Palo passed all the German checkpoints and arrived at the factory, but when their parents never arrived the boys knew they must have been caught. After a few days of hiding, the factory manager realized that he was not going to be paid and conditions were getting dangerous so he ordered the children to leave.

Without any idea where else to go, Shmuel and Palo began following the railroad tracks to their grandparents’ house 30 kilometers away. When they arrived, the house was empty. They found shelter with a neighbor for one night and then went to their aunt’s house in another village, where they stayed alone for several weeks. In October, they were caught along with three other Jews in the village by the Slovak militia and sent to the Sered concentration camp, and from there to Auschwitz-Birkenau by cattle car.

Unlike the last transport to arrive at the camp, which had been sent immediately to the gas chamber, Shmuel and the others on the train were allowed inside Birkenau with their belongings. In Birkenau, Shmuel worked with other children collecting garbage. A German guard took a liking to Palo and would bring the boys extra food from time to time and even a warm coat for Palo. Unbeknownst to them, their mother was working in the kitchen at the women’s camp in Auschwitz and another prisoner told her that she saw Shmuel and Palo in the men’s camp. On Christmas Eve, she got some sugar cubes from the kitchen and met the boys at a fence. She threw the sugar cubes over to them, but they fell into the deep snow and the boys couldn’t find them.

On January 18, 1945, the approaching Red Army triggered the Germans to begin sending the majority of the camp to go on death marches to lands that were still under German control. Shmuel, because he looked strong enough, was selected to join the march, but he immediately asked to stay with Palo since he knew they had to stay together. On Jan. 27, the Soviet Army arrived and liberated Auschwitz.

Miraculously, all four members of the Schlesinger family were sent to Auschwitz and all survived. After liberation the family immigrated to Israel in 1949, where Shmuel married his wife Eva Mayer (today Chava Schelach) and had two daughters, Tali and Limor. He was an optimistic person, never vindictive and always willing to share his stories for the rest of his life, Limor says. He passed away on August 29, 2006, from heart disease probably caused by complications from severe arthritis he developed in Auschwitz.

Miriam Friedman Ziegler

During a drive from Radom, Poland, to nearby Ostrowiec in 1939 to visit her grandparents, Miriam Ziegler Friedman’s life changed forever.

Miriam, six years old at the time, came from a wealthy family that owned and operated several large clothing and general goods stores. But on that drive, Germans started shooting at the car she was riding in, and Miriam never returned to Radom. Instead, her cousin found a Polish farmer who agreed to let Miriam hide in his barn temporarily in exchange for money. The farmer would often take Miriam with him to beg door-to-door during the day – a world apart from the life of comfort she had known just a few months before.

Miriam’s parents were forced to work at nearby factories and building sites, but they tried to keep Miriam hidden as long as possible at various houses around Ostrowiec. Her safety, however, was far from guaranteed. At one house in the Ostrowiec ghetto, she hid in the attic as every other Jew inside was shot by police. She also saw the bodies of her own cousins hung near the forest outside the town.

Eventually, her parents smuggled her into the Ostrowiec concentration camp with them, where she hid in the latrines with other children to avoid being discovered since children were not allowed in the camp. In 1944, when Miriam was nine years old, everyone in the camp was put on cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz.

Miriam was separated from her mother and other family members but managed to survive with other children until Auschwitz was liberated in January 1945. Sick with tuberculosis and an eye infection, she was sent to a series of children’s homes in Poland to recover. With no idea where her family was or if they were alive, she left a note at the train station in Krakow with her name and the names of her parents and grandparents, hoping they would find her. In fact, an old friend from their hometown saw the note and told Miriam’s mother, who came to the children’s home to reunite with her daughter. After spending time recovering in Austria, in 1948 Miriam was able to immigrate to Toronto, Canada, where she went to high school. Though her mother soon joined her, Miriam worked after school and during the summer at a bakery and a toy factory to support them.

After graduation, Miriam worked as a bookkeeper. Friends set her up on a blind date with a fellow Holocaust survivor, Roman Ziegler, whom she married in 1958. They had three children, Stuart, Adrienne and Debbie, and Miriam worked part-time in clothing stores and sold clothes to friends out of her basement. She is now a grandmother. Miriam still keeps in touch with Paula Lebovics and Ruth Muschkies Webber, who are pictured in the photograph.

Paula Lebovics

By the time the Holocaust ended, Paula Lebovics had experienced a ghetto, concentration camp, death camp and the permanent separation of her family – and she was only 12 years old.

Born in Ostrowiec, Poland, on Sept. 25, 1933, Paula was the youngest of six siblings and lived comfortably, surrounded by grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. When Paula was just 6 years old, the war began and her family was soon sent to an open ghetto a year later along with the rest of the town’s Jewish population. When one of her brothers learned a year and a half later that there would be a selection to send people to the Ostrowiec forced labor camp, Paula and her parents and siblings hid for several months, desperate to avoid capture.

Paula was briefly separated from the rest of the family while moving between hiding places and discovered by a Ukrainian soldier, who threw her against a wall so hard she was knocked unconscious. After a year and a half in the Ostrowiec forced labor camp, Paula and her family were squeezed onto cattle cars on Aug. 1, 1944, and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Paula remembers sitting on her brother’s shoulders just to be able to get whiffs of fresh air above the adults’ heads in the packed car. She was 10 years old.

At Auschwitz, Paula became a favorite of the guard of her barrack, a young Jewish woman, by singing songs, and sometimes got extra food. Every day she witnessed beatings and killings, until the approaching Soviet Army triggered the Germans to send the majority of camp inmates on death marches to lands that were still under German control. The Soviet Army reached the camp on Jan. 27, 1945, and only the children, elderly and sick were left behind. Just before liberation, the sadistic Dr. Josef Mengele offered to take the children to their families; though Paula refused, she later found the few children who had volunteered shot dead just outside the camp.

After everything she had been through, it’s no surprise that Paula remembers a ragged Soviet soldier crying as he held her in his lap when he found her in the liberated camp. He offered her his own meager rations, and for the first time in a very long time, Paula felt that someone cared about her.

Paula’s mother was liberated in Auschwitz and reunited in Birkenau with Paula, who was now 12. They spent six years at a displaced persons (DP) camp in Germany. Paula’s father and two sisters had been killed, but her three brothers survived and settled in Europe and Israel. When she was 18, Paula and her mother immigrated to Detroit. She met her husband, Michael, also a Holocaust survivor, and they married in 1957. They moved to Los Angeles and had two children, Dan and Linda, where they worked together in Michael’s jewelry business.

Now retired, Paula lives in Encino, Calif., and continues to share her story with students around the world. “Silence is not an option,” Lebovics says. “I want students to learn tolerance, to learn not to bully and not to hate.” She remains in touch with Miriam Ziegler Friedman and Ruth Muschkies Webber, her closest friends in Auschwitz, who appear with her in the photograph. The three are all from Ostrowiec.

Bracha Katz

Like several other children in the photograph, Bracha Katz (formerly Berta Weinhaber) avoided the gas chamber of Auschwitz by being one of the few selected for Dr. Josef Mengele’s medical experiments, but she was one of even fewer who survived the experiments and deplorable conditions of the camp.

Bracha was the second youngest of six siblings, born March 28, 1930, in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. Her father was descended from a long line of rabbis and was the head of the Jewish community in Bratislava. In 1942, Bracha’s three older brothers were sent to the Majdanek concentration camp, and in 1944, the rest of the family was forced into the Sered concentration camp. Just two months later, Bracha, her younger brother Adolf, older sister Rachel, and their parents were sent by cattle car to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Bracha remembers the car being so crowded she couldn’t breathe.

When they arrived on the selection platform at Auschwitz, a Jewish kapo, or supervisor, told Bracha to pretend that she and Adolf were twins, even though he was two years younger. As “twins,” they were selected for Mengele’s medical experiments block. Though Bracha did not often reveal much about what happened to her there, she remembers vividly her friendship with Eva Slonim, who is also in the photograph. Eva was also from Bratislava and the two were the oldest children in the block so they would often take care of the younger children. Using their fingers in the air, Bracha and Eva would write songs. Sixty years later, they reunited in Poland and were still able to sing a song they had written together in the camp.

Adolf became very sick and was coughing. One day, the Germans took him away and Bracha never saw him again. Someone told her that he had been shot.

Bracha survived until the Soviet Army liberated Auschwitz on Jan. 27, 1945. A man named Kon, who was a relative of Bracha’s took her, Eva, Eva’s sister Marta, and some other children to a school in Krakow to recover. Bracha continued on to Bratislava, but she did not find any family there, so she went with Eva and Marta to a hostel in the Tatra mountains. Eventually, a cousin found her there and took her to Bratislava to reunite with her mother and sister Rachel, who had been at a German arms factory.

The three planned to go to Israel together, but Bracha’s mother died of a heart attack two months before they were scheduled to depart, in 1949. Bracha and Rachel continued on, and one year later Bracha met her husband Ze’ev Katz. Bracha and Ze’ev have two daughters, Pnina and Lea, six grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Gábor Hirsch

The boy standing in the very back of the photograph (usually obscured from view except his cap, but visible in images taken from different angles) has not been identified until now. He is 15 year old Gábor Hirsch, born Dec. 9, 1929, in Békéscsaba, Hungary.

Gábor was an only child and his father owned an electrical, radio and bicycle shop. He and his parents were not very religious, and Gábor went to a public gymnasium (high school) with mostly Christian students. He remembers that some of his teachers were anti-Semitic and he was harassed by other students in one incident by the school swimming pool.

The town was occupied by Germany on March 19, 1944, and by May all the Jews had been forced into small apartments and houses near the synagogue – thousands of people in just about 100 houses. By mid-June, all the Jews were sent to the Békéscsaba ghetto, located at an old tobacco factory. Though refugees from Poland and Slovakia warned them where they might be sent next, and the horrors that awaited them, Gábor’s parents didn’t believe that such a thing was possible. Yet Gábor’s father was sent with other men to a forced labor camp, and Gábor and his mother traveled to Auschwitz by cattle car with a transport of over 3,000 people, arriving on June 29, 1944.

Upon their arrival, Gábor and his mother both survived the first selection, though they each went to different camps within Auschwitz. Gábor went to the camp in Birkenau that housed Roma and Sinti people, or “gypsies,” with his older cousin Tibor. After a few months, the entire gypsy population was murdered in the gas chambers.

Gábor was able to visit his mother at her camp twice over the next three months. The second time, he brought a piece of bread for her, but instead she gave him bread of her own, with marmalade hidden in the center. It was the last time he would ever see her; she perished a few weeks later.

He passed a few more selections, but in October the Nazis sent him and 600 others to the gas chambers. They had to undress and were inside the chamber when the officers held another examination and deemed 51 boys, including Gábor, fit for work and allowed them to leave.

Gábor grew weaker and sick. By the middle of January, Nazis had started evacuating the camp on death marches to lands that were still under German control but Gábor hid under a bunk and stayed until the Soviet Army liberated the camp on Jan. 27, 1945. He recuperated in Auschwitz and other camps before reuniting with his father in Budapest.

Gábor graduated from a technical high school and continued his studies at university. In 1956, during the Hungarian Revolution, he immigrated to Switzerland, where he graduated and embarked on an electrical engineering career. He married his wife Margrit in 1968 and they had two sons, Mathias and Michael, and two grandchildren. Gábor Hirsch passed away at the age of 90 in 2020.

The child hidden just behind Eva Slonim is Gábor Hirsch.

We spent seven months tracking down the survivors in this picture. Learn how we did it, and what we found out.

If anyone would like a copy of the original photo, please contact Bob Ahern at bob.ahern@gettyimages.com

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.