Donor enables indexing of Lithuanian testimonies, unlocking history of one of the hardest-hit countries in the Holocaust

When it comes to implementing Nazi Germany’s Final Solution, few places were more successful than Nazi-occupied Lithuania. More than 90 percent of the country’s wartime Jewish population of 250,000 was murdered in the Holocaust.

USC Shoah Foundation recorded nearly 50 Lithuanian-language testimonies detailing this devastating chapter of World War II history. But the interviews have not been indexed, due to the difficulty of finding Lithuanian speakers for the task at hand.

This is about to change. Thanks to a generous grant from the Kazickas Family Foundation – founded by Lithuanian-American businessman Juozas Kazickas – USC Shoah Foundation has hired and trained three Lithuanian-speaking indexers who have begun to delve into the testimonies. The indexing process essentially makes key moments of each testimony -- which average about two hours in length -- searchable.

In addition to paying for the indexing process, the grant also covers two additional initiatives in Lithuania:

- Bringing the Institute’s Visual History Archive of 55,000 testimonies of genocide witnesses to Lithuania in May by providing access to Vilnius University.

- Bringing Lithuanian testimonies into the classrooms of Lithuanian teens by sponsoring the creation of Lithuanian content in IWitness, USC Shoah Foundation’s no-cost educational website.

“We are deeply grateful to the Kazickas Family Foundation for this gift, which enables us to not only bring Lithuania’s testimonies to scholars around the world, but also bring our archive to Lithuania, which is reckoning with a difficult history,” said Karen Jungblut, USC Shoah Foundation’s Director of Global Initiatives.

In the summer of 1940, following a pact between the Soviets and Germans to divvy up Eastern Europe, Soviet soldiers overtook Lithuania. The communist regime nationalized private businesses, executed political prisoners and deported thousands of its citizens – many Jews included – to the gulags of Siberia.

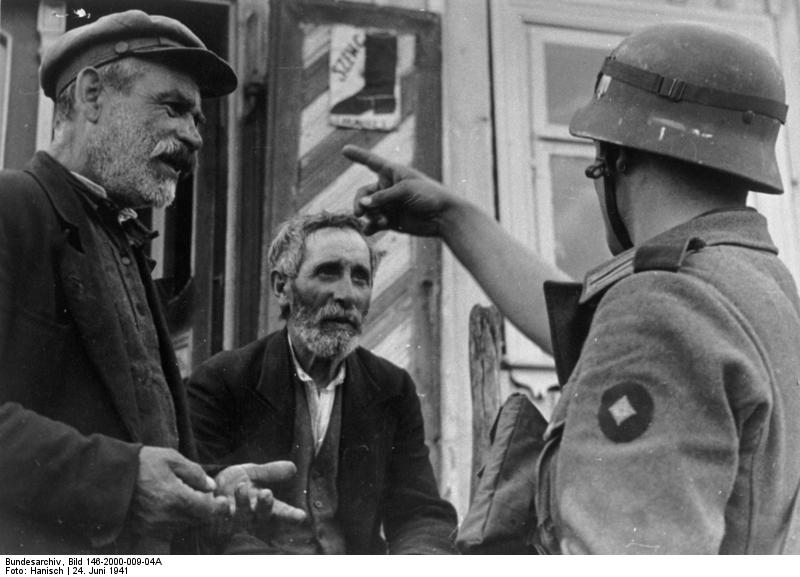

When Nazi Germany invaded a year later, some Lithuanians embraced their arrival and assisted the Germans in brutalizing the Jewish population under the pretext that Jews had sided with the Soviets. Shortly before and after the German occupation of Lithuania in June of 1941, Lithuanians began killing Jewish civilians. The frenzy reached a fever pitch with the arrival of German mobile killing units that engaged in mass shootings of Jews, whose belongings were auctioned off or looted.

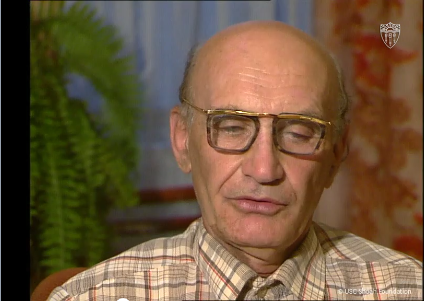

The soon-to-be-indexed Lithuanian-language collection includes some notable interviewees. Among them is Ruvin Zeligman, the sole survivor of a massacre that killed roughly 1,500 Jews in 1941, when he was 10.

Zeligman has described how his family was among a larger group of Jews herded into a cemetery by Lithuanian police, who then began to shoot at them. He saw his father fall into a pit. When Jews began to fight back, chaos ensued and Zeligman ran through a cluster of trees and across a river. He returned home to find more Lithuanian police seizing his family’s property.

Other notable interviewees include Stanislovas Rubinovas, a survivor who became a theater director; Irena Veisaite, a survivor and noted intellectual; Markas Petukhauskas, a survivor and art critic; and Vladas Varchikas, a rescuer and member of the resistance.

The project is coming together at a time when the country is grappling with the extent of its own culpability during the Holocaust. One case in particular has generated international headlines.

Last year, an American Jewish man who lost 100 relatives in the Holocaust teamed up with the granddaughter of a Lithuanian national hero named Jonas Noreika – after whom Lithuanian schools and streets are named – to set the record straight on his actual legacy. They charge that Noreika, who is lionized for his resistance to the Soviets who returned after the war and executed him, ordered the massacre of thousands of Jews during the Holocaust and moved his family into a house vacated by a Jewish family.

Lithuania marks the easternmost access point for the Visual History Archive in Europe.

In April, coinciding with the launch of the Archive at Vilnius University, librarians from the college organized a workshop to familiarize local educators, administrators and researchers with its many functions.

Andrea Szőnyi, USC Shoah Foundation’s head of programs for international education in Hungary, was on hand to give a presentation about the Visual History Archive and IWitness.

“The installation of the Archive in Lithuania will deepen the impact of Holocaust education in Lithuania,” Szőnyi said. “It will enable teachers, students and scholars here to discover events that occurred in their local regions, as told by the survivors and eyewitnesses whose stories until now were often missing from the public record.”

This collection of Lithuanian-language interviews – as well as another collection of 137 additional interviews in other languages that were conducted in Lithuania – has also received financial support from Leesa Wagner, a member of the Institute’s Next Generation Council, and her husband Leon Wagner.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.