Personal stories of surviving the Holocaust unveiled at powerful art exhibition

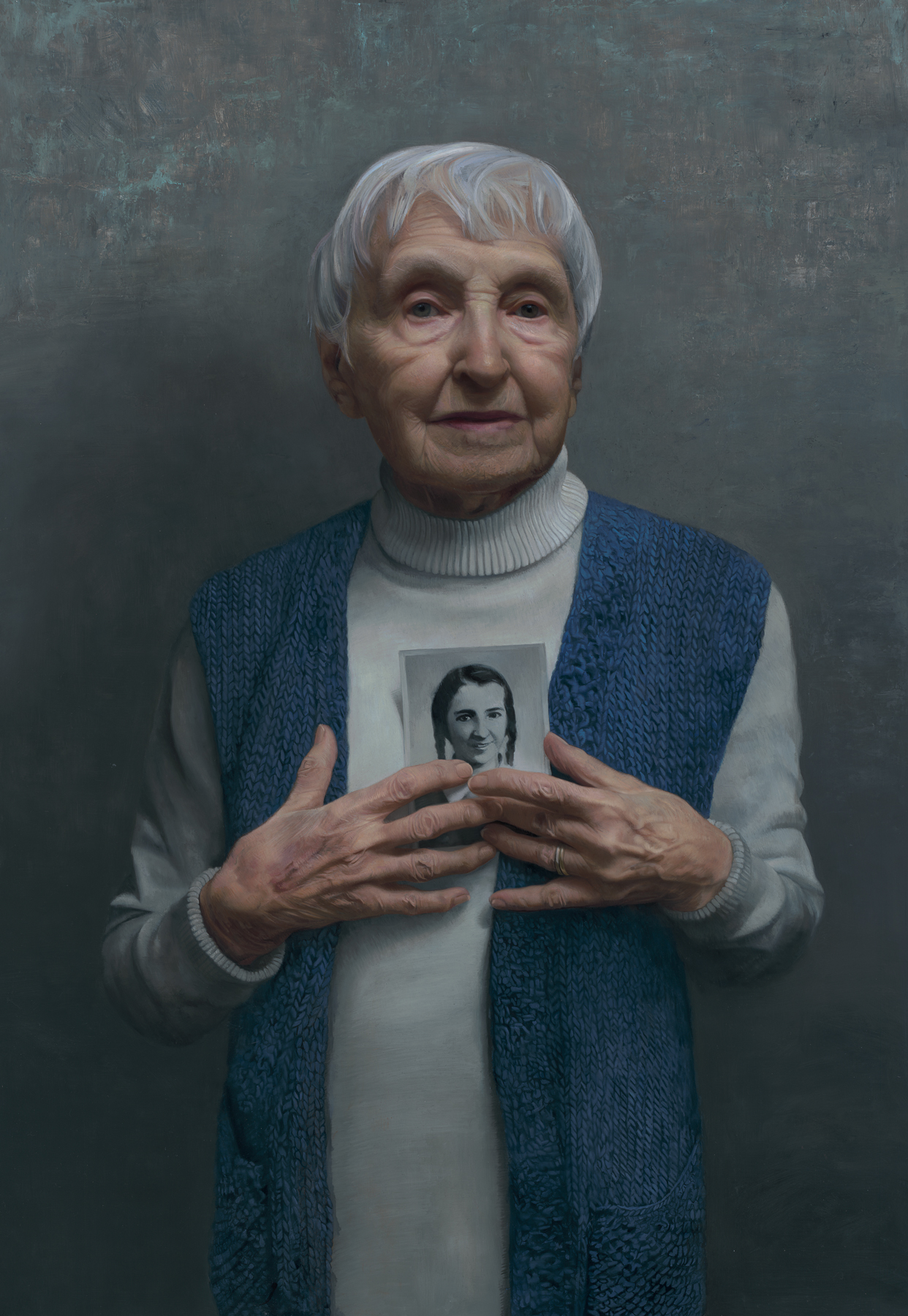

Painter David Kassan has sat with survivors of the Holocaust for countless hours during the past five years, carefully listening to their stories of pain, grief, resilience and quiet victory.

He has grown to know them intimately, learning about how they viewed the traumatic experiences of their youth and their journey in the years that followed. That deep knowledge is critical for him to do his work: preserving their memories through portraits.

Now the public can see those strikingly personal paintings, and hear the stories behind them, during a new exhibition at the USC Fisher Museum of Art. The show, Facing Survival | David Kassan, pairs dozens of the artist’s poignant and lifelike portraits with a life-size display from USC Shoah Foundation — The Institute for Visual History and Education. The high-tech screen allows visitors to ask survivors, including several featured in Kassan’s artwork, about their life before, during and after the genocide and hear their prerecorded replies.

“We are taking art and using it to honor human memory at times when it is so difficult because it’s so painful,” said Selma Holo, director of the USC Fisher Museum of Art and professor of art history. “Art is a kind of knowledge, and when you put it together with other kinds of knowledge and technology, you create something very special.”

The exhibition runs from Sept. 18 to Dec. 7 at the art museum on the University Park Campus. It’s a culmination of Kassan’s residency with the museum and USC Shoah Foundation that started in 2017, as well as a showcase of the realist painter’s ongoing efforts to capture both the appearance and essence of people who survived the Holocaust.

About a dozen of the survivors portrayed in the paintings came to an opening reception on Sept. 17. Speaking at the event, USC President Carol L. Folt said it was an honor to meet the survivors in person.

“My heart is full, just being here,” she said. “The Fisher Museum is a gem and I plan to be here many times. I know that art can speak about things that we can’t say so easily with words.”

Folt added that USC Shoah Foundation is “one of the great points of light in the world right now.”

“It bears witness to the unthinkable,” she said, “yet it also tells the stories of people, and is so filled with life and hope and meaning.”

Like the thousands of hours of video interviews with genocide survivors captured and maintained by USC Shoah Foundation, Kassan views his work as a form of testimony about their experiences.

“They are so different — it’s the spectrum of humanity,” Kassan said. “Some people say, ‘Oh, it was just a thing that happened.’ Some people still think about the camps every day. It’s a personal story that can speak to somebody. Maybe it can speak to a Holocaust denier who now sees the humanity in these people.”

Haunting personal narratives of Holocaust survivors come to life in USC exhibition

Ask Pinchas Gutter what he ate while being held in the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland decades ago, and he will describe how he and his fellow prisoners might receive a cup of tepid water steeped with acorns for breakfast. For lunch and dinner, they’d swallow a thin soup with old potatoes and if they were lucky, a few pieces of tough, spoiled meat.

He recalls the way his twin sister’s golden braided hair shimmered in the sun as she was separated from him with the other girls and women. It’s the last memory of her he carries. Nazis murdered her with the rest of his family in the camp’s gas chambers.

Gutter also remembers the day he awoke in another concentration camp, Theresienstadt, and discovered the guards had abandoned their post. He cautiously crept through the gates and found a horse and cart, unattended. He rode away from the grim prison toward the nearest town — and his freedom.

Those intimate details and many more are captured in perpetuity through USC Shoah Foundation’s Dimensions in Testimony, the interactive interview project that has collected more than 20 life stories from Holocaust survivors.

Gutter’s image is among those on display at the art exhibition, available for visitors to ask questions and learn more about his experiences during and after the war. His likeness is also rendered in paint on canvas, his soft blue eyes and the creases around his mouth carefully shaped by Kassan’s brush.

Artist strives for humanity in portraits of Holocaust survivors

Kassan is known for his raw and unvarnished approach to portraiture, which he describes as an effort to bring forward the emotion and personality of his subjects.

“I’m very much about documenting the realistic aspects of a person, the luminosity of their skin and all that, but also getting at the deeper aspects of their pathology,” he said. “It doesn’t necessarily make people look pretty; it’s not always flattering. But sometimes people say, ‘Wow, that’s exactly who I am.’”

Showing those wrinkles on their faces and hands honors the survivors’ physical resilience, said Stephen Smith, the Finci-Viterbi Executive Director at USC Shoah Foundation. It also speaks to the long lives they have led after the trauma of the Holocaust.

“Kassan places them far out of reach of the Nazis and their destructive genocidal world,” he wrote in a catalog that accompanies the exhibition. “In the portraits, it is clear that these individuals outlived their oppressors and are no longer victims. They are dignified. They display no anger or bitterness. There is wisdom and depth in their eyes. They tell a story with no words.”

Holo, who curated the show with Smith, elaborated: “David is interested in seeing if he can expose a soul. So he keeps going deeper and deeper. What shows is what they want to reveal to him, and he’s honoring that.”

Portraits bring personal side of genocide to light

Kassan’s Holocaust survivor series started when a collector asked him to paint a portrait of his mother-in-law. Although he rarely takes commissions, Kassan became interested when he learned she had survived the Holocaust. Although she eventually decided not to sit for a painting, the idea took root in his mind.

Soon, Kassan had connected with other survivors in New York and New Jersey. His first portrait in the series is of Sam Goldofsky, who survived Auschwitz and a death march. In the painting, Goldofsky stares into the distance, the fading and blurred lines of his concentration camp tattoo visible on one of his crossed arms.

“His story is really intense,” Kassan said. “We met and did the interview, and at that point I thought: This is a worthy subject.”

Kassan said curiosity about his background also played a role in his desire to paint survivors. Although ethnically Jewish, he wasn’t raised in a religious home and wanted to learn more about his family roots. He also found insight into the experiences of his paternal grandfather, who escaped ethnic cleansing on the border of Romania and Ukraine and emigrated to America in 1917.

The artist continued working on his portraits for several years, traveling the globe to meet and interview people who lived through the Holocaust. Then he was invited to Los Angeles to meet with survivors through the Museum of Tolerance. When Kassan learned that a group of survivors of Auschwitz met regularly at the museum, he decided to create a large portrait featuring 11 of them. The resulting 18-feet-wide canvas, which he painted in sections over two years in his studio in Albuquerque, N.M., is arguably the centerpiece of the USC exhibition.

“I wanted to do something indelible, something impossible to ignore,” he said.

Facing Survival show prompts visitors to reflect on humanity

Several years ago, when an artist friend introduced Kassan to Holo, the USC Fisher director quickly saw the potential for a collaborative show with USC Shoah Foundation. She helped raise money for his residency at USC, and the museum purchased one of his portraits for its permanent collection.

Kassan and the curators decided to name the USC exhibition Facing Survival because of its multiple meanings.

“I’m putting faces to survival,” Kassan said. “The people who view the show are facing the survivors. The subjects had to face what it meant to survive, to have survivor’s guilt.”

Holo is hopeful that visitors will take time to engage with each portrait and explore the interactive display. Statistics about the Holocaust — such as the millions of deaths that occurred — can be difficult to comprehend or digest on their own, she said. But practicing what Holo calls “slow looking,” including hearing and seeing personal stories, can help people develop meaning around the genocide, she said.

“It’s very important for us not to lose touch with the basic ways we represent humanity,” Holo said. “Storytelling is extremely important. Things happen randomly, but if somehow you piece it together into a story, people have a better chance of it imprinting on them. We’re honoring the old way of telling stories and then joining it with these new techniques that can make it even more accessible.”

Editor's note: This article first appeared on USC News.

By Eric Lindberg

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.