Attack on Ukraine Summons Haunting Echoes of the Past

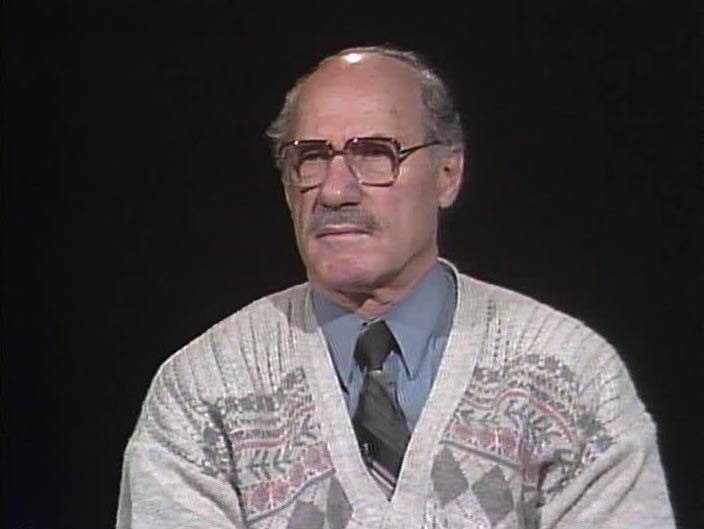

Above, Alex Redner with his grandparents in 1937 in Lvov

As the world watches in horror as millions of Ukrainians resist, take shelter or flee from Russian attacks, news reports stir up connections to a haunting past. For many, images of fear and flight from places like L’viv, Kyiv, Donbas, Odesa and Babi Yar summon echoes of the unspeakable inhumanity of the Holocaust.

We scanned our Visual History Archive to bring just a few stories from these places to light. The words of survivors, as they often do, reach forward through time.

Tainted Miracles in Odessa

To Helen Helfant, Odessa felt like a godsend.

To Helen Helfant, Odessa felt like a godsend.

In 1940 Helen and her husband had staged a daring midnight escape from Nazi-occupied Warsaw into Soviet-occupied territory. But they were arrested and banished to a settlement in the forests of the remote Soviet autonomous Republic of Komi, where for four long winter months, they spent their days chopping trees and passed their nights in a windblown shack, fueled only by a daily ration of 600 grams of bread and a bit of watery soup.

Helen and her husband were again able to escape, this time in the spring of 1941 when they trekked into the dense forests of Komi, and then beyond.

“We crossed Russia from the north to the south, mostly running on foot, and partially by train,” Helen said in testimony recorded in 1995. Within a few weeks, they had covered 2,500 kilometers.

“And then we reached Odesa … It was like a miracle, because over there was a warm climate. That is what we were crying in a fantasy, just to reach a warm climate, because we were so much frozen in the Siberian town,” she said.

Helen and her husband both found jobs, and a widow rented them a room in her apartment.

But then, just a few months after they arrived, on June 22, 1941, Hitler attacked the Soviet Union and Helen’s husband was conscripted into the Red Army.

“And Hitler started the bombardment of the city. It was such a beautiful city, Odesa. I will never forget, a beautiful city. And he was destroying the city part by part, again the same thing like in Warsaw, a repetition of Warsaw. There was no light, no water, there was nothing to eat,” she said.

One night, Helen joined a line outside a warehouse to get sugar, oil, bread – whatever the communist government might be offering. She stood in the snaking line from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., but then realized she had forgotten to bring a jar with which to carry some oil. She asked someone to hold her place in line while she ran back to her nearby apartment.

When she returned 15 minutes later, the line had been decimated.

“It was a terrible bomb that they threw on this line. When I came down, I didn’t recognize anybody – there were hands and legs and heads. The whole line, about 800 people, got killed. If I wouldn’t go for this bottle, I would have got killed the same,” she said. “I don’t believe in miracles, but somehow, it happens in life things that you can’t imagine how it happened.”

Horror in Kyiv

Samuel Orshan lived with his parents, his younger brother, and a large extended family in a Kyiv neighborhood near what was known as the Jewish Market.

Samuel Orshan lived with his parents, his younger brother, and a large extended family in a Kyiv neighborhood near what was known as the Jewish Market.

He was 11 years old on June 22, 1941, when Germany launched a massive attack on the Soviet Union.

“There was bombing all around us,” Orshan recalled in his testimony. “We lived not far from a big factory and they bombed that factory, so we could hear the explosions, too.”

The attacks went on for months. Samuel remembered standing on the roof to watch the explosions as his mother screamed for him to come down to the bomb shelter.

One night in August 1941, Samuel’s father, who was serving in the air defense unit of the Red Army around Kyiv, showed up with a truck and told the family to pack. He had spent the previous month planning how to get his family to safety before the city fell under Nazi control. That night he drove his family to the cattle train that would evacuate them, and left to rejoin his army unit.

Samuel, his mother and brother were sent to the city of Kizlyar, in today’s Republic of Dagestan, and then to a nearby farming village. Samuel cared for his brother while his mother worked in a hospital. By the end of September 1941, they heard that Kyiv had fallen to the Germans and received the news that Samuel’s father was missing in action.

A few months later, a neighbor from Kyiv turned up injured in the hospital where Samuel’s mother worked as a nurse. He told them that immediately after the Nazis occupied Kyiv, in September 1941, all of the Jews in Kyiv and the surrounding areas had been rounded up and forced to march to Babi Yar, a ravine near the old cemetery. He said he had seen Samuel’s father there before managing to slip away from the human column and hide in a courtyard. Almost no one else managed to escape the ensuing massacre, the neighbor said.

As the German army advanced south in 1942, Samuel’s family was evacuated to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. There they were housed in a large hall with more than a dozen other families. Samuel’s mother found work while his brother started kindergarten. Samuel tried to talk his way into a military academy, but instead had to settle on trade school.

In December 1943, the Red Army recaptured Kyiv after a prolonged battle with German forces. Samuel, then 14, knew what he had to do.

“I couldn’t stay anymore in Tbilisi. I wanted to go home and fight Germans,” he said.

He left his mother and brother and headed for Kyiv—nearly 2,000 kilometers away—by hopping trains and hitching rides with sympathetic military transports.

He arrived in battle-scarred Kyiv in the spring of 1944. To his great disappointment, the army would not take a boy as young and lanky as Samuel. So, instead, he lived with an aunt and uncle and again enrolled in a trade school.

Samuel later learned that about 20 members of his family—including his father—were among the 34,000 Jews killed at Babi Yar over a two-day period in September 1941.

Waves of War in L’viv

As a young boy, Alex Redner lived through three waves of occupation in his native L’viv (then Lwów, part of the Second Polish Republic): A German invasion followed swiftly by Russian occupation in 1939; another German invasion in June, 1941; and then Russian liberation and occupation in July, 1944.

As a young boy, Alex Redner lived through three waves of occupation in his native L’viv (then Lwów, part of the Second Polish Republic): A German invasion followed swiftly by Russian occupation in 1939; another German invasion in June, 1941; and then Russian liberation and occupation in July, 1944.

Before all that, Alex had enjoyed a good life. His father was a respected doctor, with patients from many backgrounds. Alex had an older sister, Emily, and a large extended family.

Alex was 11 when Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939,

"We had hundreds of refugees fleeing from west to east, and the roads were simply filled end to end with people trying to run away,” he said in his testimony.

Within a few days the German military campaign had reached L’viv, which was on the far eastern side of Poland.

“We had daily bombing of German planes. We were practically living our days and nights in a basement shelter,” Alex said.

On September 17, 1939, Germany handed L’viv to the Soviet Union as part of a secret pact between Hitler and Stalin, and the city, with its large populations of Ukrainians, Poles, Jews and Russians, came under Soviet control.

L’viv rapidly filled with refugees from Poland who wagered that life under Stalin would be better than under Hitler. The Redners made room in their apartment for friends, relatives, and even strangers seeking shelter.

Then, on June 22, 1941, German planes bombed the city and on July 1, its troops occupied L’viv.

“From the very first day, it was an abysmal situation. It was like being thrown from a normal life down in the pits and becoming a rat trapped in the bottom of a pit. That was that big of a change,” Alex said.

Nazi attacks on the city’s Jews began immediately. Alex and his family were able to evade several roundups and deportations, but his grandfather was killed. The family lived in and out of hiding using false papers and spent many months in the L’viv ghetto. When the Red Army liberated L’viv in July 1944, they were hiding in a village 20 miles from the city.

When they went back to L’viv – one of only a handful of Jewish families to return – they found that their apartment had recently been vacated by Germans. The Redner apartment became a stop for the many Jewish refugees who arrived in L’viv.

“I remember that we had, day after day, people with a tea in hand telling us the story how they eventually escaped, and they came back to Lwów. And we didn't have any good news for anybody,” he said.

The Redners left L’viv in 1946, and Alex made his way to France, where he met his wife, then moved to Uruguay, where his parents were living. He and his wife and two daughters ended up in Pennsylvania.

When he gave his testimony in 1995, he had these cautionary words.

“I think that the lesson that we all should remember is that we are surrounded by a very dangerous world,” he said. “If Hitler succeeded to make out of Germany a nation of criminals in a little time, through a very shrewd effort of propaganda, that same thing can be done in very many other places, in much less time, with the help of television and modern technology. ... We should be prepared to somehow deal with it the moment it happens.”

As war breaks out, we stand by our programmatic partners in Ukraine and Russia working to build more tolerant communities.

Emiliia Kessler grew up in Khmel'nik, then part of Soviet Ukraine. Watch as she recalls the complex tensions between the Russians, the Ukrainians and the Jewish community that were part of everyday life in the 1930s.

Our Russia and Ukraine experts spoke with Annenberg Media.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.