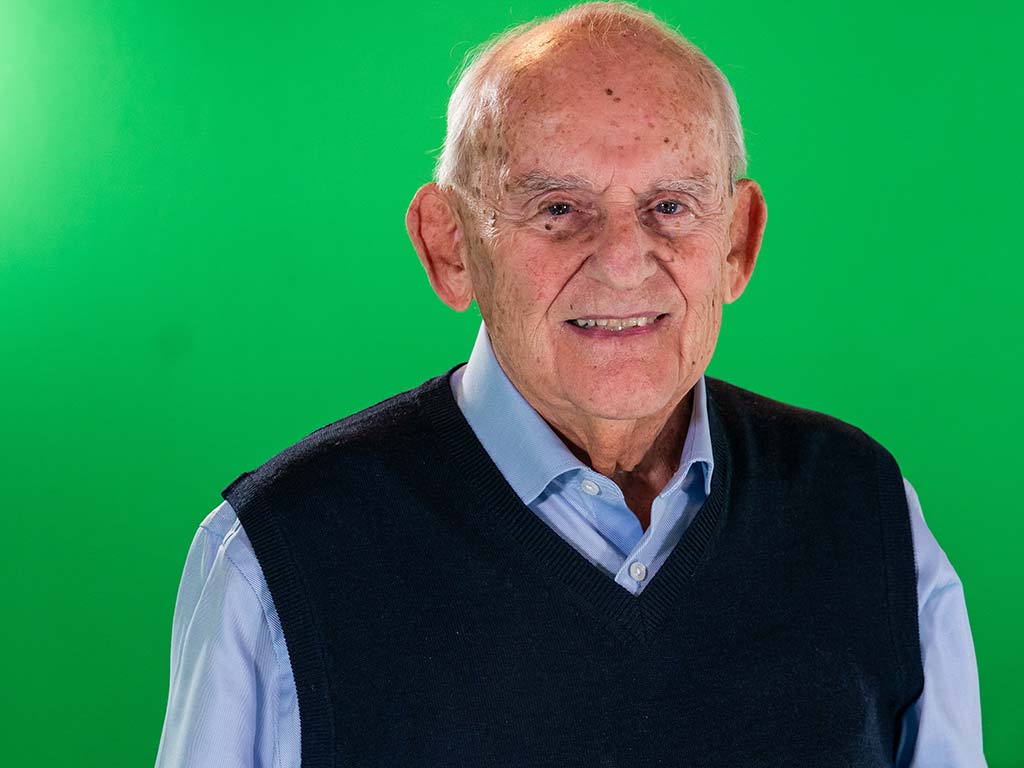

We Remember Concentration Camp Liberator Alan Moskin, 96, Advocate for Holocaust Education and Remembrance

USC Shoah Foundation is saddened by the passing of Alan Moskin, a Jewish veteran of the U.S. Armed Forces who, at the age of 18, helped liberate Gunskirchern, a subcamp of Mauthausen Concentration Camp, in May 1945. Later in life, Alan became a tireless advocate for Holocaust education and remembrance at schools, veterans’ groups, and in the media, speaking with candor about the horror he witnessed at the camp, the brutality of combat, and the bigotry he encountered in the U.S. Army.

Alan, who was close to his 97th birthday when he died, was featured in the award-winning 2020 documentary Liberation Heroes: The Last Eyewitnesses, which was produced for Discovery Channel in association with USC Shoah Foundation.

“Alan was and is a powerful inspiration and voice who was able to connect in a special way with everyone from young cadets to other veterans,” said Andy Friendly, a member of USC Shoah Foundation’s Board of Councilors who produced Liberation Heroes with June Beallor, USC Shoah Foundation’s Founding Executive Director.

“Alan touched so many people with his warmth and honesty and was a courageous champion of humanity. He has left an indelible imprint on all of our hearts,” Beallor said.

In 2021, at the age of 95, Moskin became the first American veteran and first liberator to record testimony for Dimensions in Testimony, the Institute’s pioneering interactive biography exhibit that enables people to prompt real-time responses from video interviews. Alan’s Dimensions in Testimony interview was on view at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans in 2021, and more than 2,000 students have interacted with his testimony through an educational partnership with Common Circles.

In 2019 he also told his story as part of USC Shoah Foundation’s Last Chance Testimony initiative. The three-and-a-half-hour video interview is now indexed in the Visual History Archive, along with more than 56,000 testimonies of survivors and witnesses to the Holocaust and other genocides.

Born to a Jewish family in Englewood, New Jersey in 1926, Alan Moskin was raised in an ethnically and racially diverse community where his father, a pharmacist by profession, served as mayor for many years.

A student at Syracuse University, Alan earned the nickname “college boy” when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in October 1944, at the age of 18. He was sent for basic training to Camp Blanding in north Florida, his first exposure to racial segregation in the South.

In his barracks, he pinned up a photo of himself and teammates with arms around each other after winning a basketball game. The photo included a few Black friends.

“I got along with Southern boys initially, but when they walked by, and they start seeing that picture that I put up, they got very upset and said, ‘Is that you, college boy?’” he recalled. “I didn’t get why they were so angry…Their whole attitude toward me went down after they saw that photo.”

Moskin himself was also subject to antisemitic taunting.

“I said to myself, ‘this is America?’ I’m going over to fight the Nazis, the bad guys, and I’ve got guys on my team, so to speak, thinking and talking and acting like this? It was very disturbing to me.”

However, once they were deployed to Europe in January 1945, Alan said, “In combat I’ve never experienced any of that. We didn’t care if you’re white, Black, Jew—none of that in combat.”

Alan was a member of the 66th infantry, 71st Division, part of General George Patton's 3rd Army. His outfit landed in Liverpool, England and was immediately sent to France. He fought on the frontlines in France, Germany, and Austria, during which time he was promoted from private to staff sergeant. During those few months of brutal and bloody combat, Alan made and lost many friends. He saw his best friend killed by shrapnel, and his sergeant asked him to write a letter to the soldier’s mother.

“I still think about him when I talk about it. It's 75 years ago, and I still, when I talk about it, I feel it like it's happening over again,” Alan said.

Toward the end of the war, his unit captured a number of Nazi prisoners. One, a large, blond German soldier in shackles, approached Alan and screamed and spat in his face. Alan raised his rifle to the man’s neck. A major shouted at Alan to stop, warning him that he risked being court martialed.

“This Nazi's cursing me and spitting in my face, but thank God for the major. I kicked the Nazi in the butt and put the rifle back down,” Alan recalled.

On May 4, 1945, Alan’s outfit entered the Gunskirchen Concentration Camp in Austria, a sub-camp of Mauthausen.

Before he laid eyes upon the camp, he detected a horrid stench, “one that never leaves your mind once you smell it.”

Alan and his whole regiment were horrified and sickened at the piles of corpses and emaciated prisoners they encountered. His commanders radioed for humanitarian aid.

A man in a prisoner’s uniform with open sores and lice crawling across his body learned that Alan was Jewish. The man bent to kiss Alan’s muddied boots, and Alan lifted him to standing. The two embraced and cried.

In his testimony, Alan recalled the orders delivered by his captain, in the name of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe.

“I want you to take photos, I want you to get everything down, I don’t want my ‘grunts’ to pick up those bodies. I want you to bring people in from town…bring the trucks, let them see the bodies, make them put them on the trucks, because someday people are going to say we made it up. They won’t believe it.”

Alan served in the army of occupation in Austria until June 1946, working in the postal service and spending time in displaced persons camps helping survivors search for family members.

During that time, he attended the Nuremberg Trials, which interested him because he planned to later attend law school. The testimony he heard from witnesses horrified him, including that given by people who had witnessed and participated in Nazi Joseph Mengele’s so-called medical experimentation.

“It was shocking, it was unbelievable,” he said.

After returning to New York, Alan graduated from New York University Law School, going on to serve 20 years as a civil trial attorney and then in private practice until his retirement in 1991. He married his wife Christa in 1967, and the couple had two daughters, Jackie and Lisa. They divorced in the 1980s and remained close friends.

Alan was always reluctant to revisit the brutality he had seen in Europe, but as Holocaust denial became more prevalent over the years, he remembered Eisenhower’s foresight in forcing local residents to witness the horror of the concentration camps. And so, 50 years after the war and after turning down many overtures, he finally decided to add his own voice and began speaking at schools about his experience, connecting with hundreds of thousands of students and adults in vivid and intimate talks over the years.

“Let's be honest. In another five or 10 years at the outset, you're not going to see anybody like me, the liberators, the survivors, the hidden children, the Kindertransport, the righteous—we're going to be gone,” he said in his 2019 testimony. “So they've got to remember what they heard here and tell their children and grandchildren what they heard so that history doesn't repeat itself.”

In addition to his testimonies for USC Shoah Foundation, Alan made video recordings at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City and the Holocaust Museum and Center for Tolerance and Education in Rockland Country, New York, where he served as Vice President of the board of trustees. He participated in programs at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and is a past Commander of the Rockland/Orange District Council of the Jewish War Veterans of the U.S.A and an inductee in the New York State Senate Veterans Hall of Fame.

Alan Moskin was buried with military honors at the Frederick W Loescher Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Spring Valley, New York on April 19. He is survived by his daughter Jacqueline Moskin Corcoran and her husband Hugh, daughter Lisa Moskin, seven grandchildren and his former wife Christa Moskin.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.