NEH Grant to Fund Transcription, Translation of Guatemalan Genocide Survivor Testimonies

A longtime scholar affiliate of the USC Shoah Foundation has received a $50,000 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant to transcribe and translate the Maya-Kaqchikel and Spanish-language testimonies of survivors of the Guatemalan genocide.

The NEH grant will enable a team led by Dr. Brigittine French, Professor of Anthropology and Assistant Vice President of Global Education at Grinnell College, to make the Maya-Kaqchikel- and Spanish-language testimonies accessible in written form for the first time. The grant will also enable some of the oral histories to be translated into English.

The 76 Maya-Kaqchikel- and Spanish-language testimonies to be transcribed and translated are a subset of the 830 oral histories collected by The Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala (FAFG) since 2015. To date, close to 600 of the FAFG testimonies have been digitized by the USC Shoah Foundation, with 32 of these integrated into the Visual History Archive (VHA), where they are available in their original languages. The remaining digitized testimonies are not publicly available due to funding constraints.

Professor French’s project, “Maya Testimonies in the Visual History Archive: Transcribing, Translating, and Accessing Survivor Life Histories," is a collaboration with the USC Shoah Foundation. Once the project is completed, the transcripts and translations of this subset of testimonies will be available for research and education, including through a range of activities on IWitness.

The Guatemalan Genocide refers to the killings of civilians, the vast majority of whom were Indigenous Maya rural farmers, as part of counter-insurgency military operations during the 1960-1996 Guatemalan Civil War. An estimated 200,000 people were killed by the military and paramilitary forces during the conflict.

Dr. Badema Pitic, Acting Head of Research Services at the USC Shoah Foundation, said the NEH grant will enable Professor French and her team to make Guatemalan genocide testimonies more widely available to researchers, educators, and students around the world.

“The new transcriptions are a critical first step in bringing the voices of Guatemalan genocide survivors to a wider audience,” Dr. Pitic said. “Once complete, they will enable in-depth and fine-grained research, analysis, as well as subsequent translation into English.”

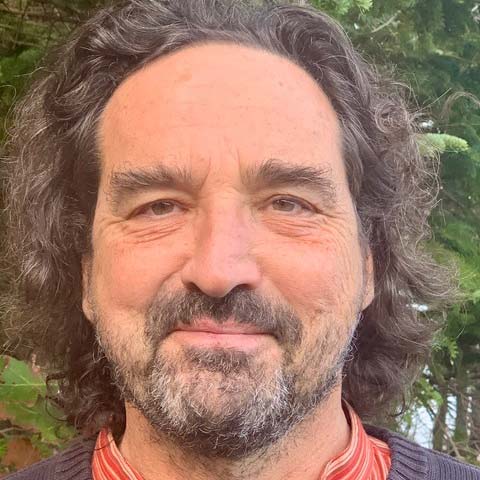

Professor French earned her BA, MA, and Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Iowa. She is a linguistic anthropologist interested in ethnonationalism, post-conflict states, testimony, collective memory, and discourse analysis. Professor French sat down to discuss the NEH grant, the importance of testimony, and how the partnership with the USC Shoah Foundation will help shine a light on an often-overlooked violent history that took place in the Americas.

Tell us about the FAFG testimonies in the Visual History Archive

The FAFG testimonies in the Visual History Archive are extremely important in the context of what we know, what we say we can know, and the evidence we have about the genocide in Guatemala.

And here is some context as to why: When the Guatemala peace accords were signed in 1996 there were two consecutive truth commissions that set about to collect testimony from survivors. The first was sponsored by the Catholic Church, and the second by the United Nations. The United Nations Truth Commission [La Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico, CEH] subsequently published a nine-volume report, Memory of Silence, in which one of the key findings was that, unequivocally, there had been acts of genocide committed against the Maya population in Guatemala.

One of the reasons why the Visual History Archive testimonies are so important is that even after the U.N. found clear evidence that acts of genocide had been committed, many segments of Guatemalan society—and arguably even abroad—contested the fact. So, one of the profoundly important things that the testimonies housed in the VHA establish, reestablish, and demonstrate is that genocidal acts were committed against Maya peoples. They provide concrete descriptions and first-person details on what parts of the country these acts took place in, who the actors were, and how they managed to survive. So even though when we think about the VHA, we're very much thinking about public education and research, there is this additional element that answers clearly those who still contest the genocide ever happened.

How much of an appetite is there in Guatemala for examining this painful chapter in the country's past?

I would say there is a tremendous amount of interest in Guatemala in engaging with, understanding, and bringing to light all of the memories and experiences that are still silenced in the public record, in public discourse, and even in local communities where sometimes folks live next door to perpetrators who may have been involved in the death or disappearance of their family members.

[But] interest in Guatemala [also] has to be understood in the context of the tremendous amount of fear people have about discussing these issues. So while there's interest, there is fear around what happens if you do [discuss these things in certain contexts]. That’s because post-conflict Guatemala in 2023 is a place where impunity for crime still structures the legal system, it still structures people's expectations about everyday life. And because impunity for crime—including the genocide—is so prevalent, if someone were to retaliate against a victim for talking about the genocide, that victim wouldn’t necessarily feel that they would be protected.

So the fact that these testimonies have been taken by Guatemalans in Guatemala but then also deposited in the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive means there is an additional degree of safety and protection in that folks can [and will always be able to] access them securely.

Tell us about the $50,000 NEH grant you’ve just received to transcribe and translate the 76 testimonies in the Visual History Archive

The particular testimonies I'm working on with my colleagues in Guatemala are offered by Indigenous Maya Guatemalans. Why Indigenous Maya Guatemalans? Because these are folks who are not only victims of state-sponsored terror—[as, of course, were hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans]—but they were also specifically targeted for extermination in terms of being a recognized racialized group in Guatemala. Simply put, we've seen in lots of ways that the genocidal intent of the army was to exterminate “the Indians.”

There are 22 recognized Maya ethno-linguistic groups in Guatemala, many, but not all, are represented in the VHA testimonies. We are honing in on the Maya-Kaqchikel- and Spanish-language testimonies because we have native speakers of these languages on our team who lived through those experiences and have academic and technical expertise working with linguistic data. These are the materials that we can do the best job on, with some depth. This is a trial, and once we’ve produced these transcripts, we’ll hopefully be able to scale up to other Maya groups in the future.

What will transcribing and translating these oral histories mean?

Among many other things, it will help spread awareness about this event in the U.S. and the Anglophone world.

The testimonies make histories that are forgotten and unknown visible alongside genocides that we are more familiar with, such as the Holocaust. When we think of the Holocaust and the work of the USC Shoah Foundation, the ethical imperative is to never let genocide happen again. So to show the ways that these patterns of racism and discrimination and extermination were perpetrated in Guatemala is of paramount importance.

Do you think that more people in Guatemala are interested in giving testimony?

Yes, absolutely. As I've been working on this with my Maya colleagues, it’s interesting to see how often people—unsolicited—start sharing their experiences with us. People are eager to share what they went through when they know they can trust the folks who they are speaking to. The fact that forensic anthropologists have done this collection and that the material is in the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive is a marker of safety and legitimacy. It shows that other folks are listening and paying attention inside and outside of Guatemala and the United States.

A short introduction to the Guatemala Genocide collection preserved at the USC Shoah Foundation can be viewed here:

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.