Women at Nuremberg: Harriet Zetterberg

Editor’s Note: Narratives surrounding the Nuremberg Trials overwhelmingly focus on the men. From U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson to the notorious Nazi leader Hermann Goering, the legacy of this landmark event in judicial history is framed by men, overshadowing the critical and diverse roles played by women.

USC Shoah Foundation is spotlighting the under-examined efforts of women at Nuremberg in an eight-part series of stories that each focuses on the contribution of a different woman. The stories were shared in a Jan. 30 public lecture titled “Women at Nuremberg” by Diane Marie Amann (University of Georgia), who came to work at the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research as a fellow in January.

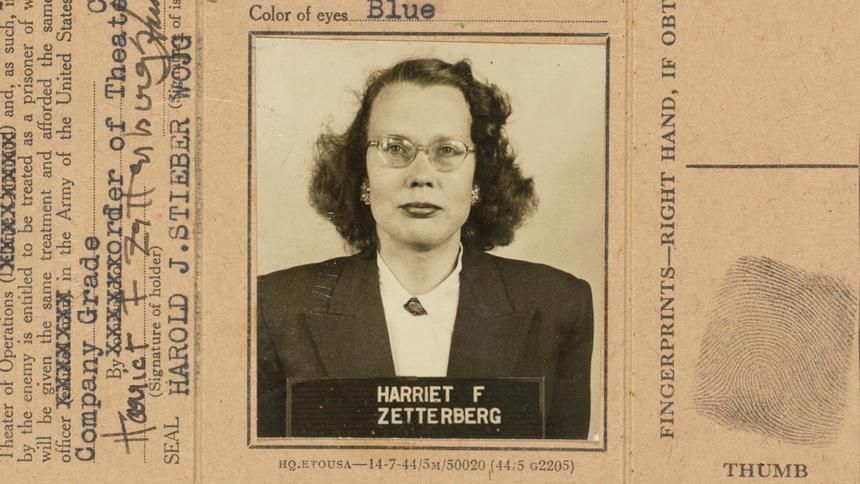

Harriet Zetterberg

Harriet Zetterberg

As a lawyer at the Nuremberg Trials, Harriet Zetterberg made a breakthrough: She unearthed a photo proving a doctor’s association with Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler. This led to the conviction and 20-year sentence of the doctor for his role in the Holocaust.

And yet, as the only woman on the prosecutorial staff -- despite her expertise and credentials – she was allowed only to write briefs, not present them to the court.

“Those were the days when you didn’t consider women taking a very prominent part,” said Zetterberg’s husband, Daniel Margolies, in his 1997 testimony with USC Shoah Foundation. “Which she rather resented.”

Zetterberg died in 1986, nearly a decade before USC Shoah Foundation was founded. But some of her accounts of the experience were recently published in the newspaper of her hometown in Valley City, North Dakota.

“Travel is very difficult, since all the facilities are pretty much broken down and plane travel out of Nuremberg is sketchy,” she wrote in a letter to her mother from Nuremberg, Germany. “The ruins get a bit depressing."

After graduating from Valley City High School, Zetterberg earned a bachelor’s degree at Carleton College and a master’s degree at Wisconsin University. She studied law at Yale University.

Zetterberg first arrived overseas in London with the Economic Warfare Division in 1944 as an employee of the State Department’s legal team. One year later, she would transfer to the War Crimes Commission.

In Nuremberg, there was a restriction on husbands and wives living and working together during the trials. Zetterberg and Margolies – who worked as a research assistant for the prosecution – found a loophole: They lived together, keeping their relationship from their co-workers. “Living in sin,” Margolies said, was more acceptable than living together as husband and wife.

As an attorney at Nuremberg, Zetterberg was tasked with assembling data from the diary, speeches and other records of Hans Frank, Hitler’s personal lawyer.

Frank, who later became governor of a part of Poland, "was a pretty frightful character,” Zetterberg wrote to her mother, Mary Zetterberg, in January of 1945. “I've been stringing together passages from the diary to prove that he advocated and supported all the criminal policies of his administration. You might say he dug his own grave with his fountain pen."

Zetterberg was struck by enormity of Frank’s crimes.

"It makes me feel inadequate trying to put something of Hans Frank's crimes into record; it's too vast ever to condense into a trial brief,” she wrote. "In fact, what is said in Nuremberg can only be illustrative. The terror and tragedy of Nazi oppression is beyond imagination and certainly beyond the powers of anyone here to adequately describe."

Frank was ultimately convicted and executed.

Zetterberg also wrote about other infamous defendants, whom she faced every day.

"The defendants are beginning to look quite haggard," she wrote her mother; "Even (German Gen. Hermann Göring) shows signs of wear and tear; not at all the cheerful cherub he was when I watched him (being interrogated) six weeks ago.

"(Rudolf) Hess is thin and nervous, with a greenish pallor.

"They are all a thorough contrast to the pictures that were shown yesterday of the Nazi hierarchy at the height of its power.”

When Zetterberg became pregnant, the prosecution made arrangements for her and Margolies to travel to the United States.

“There were a number of wives of soldiers at that time – they got married in England or in Europe, and those wives were all sent home,” said Margolies, who died in 1999 at age 89, in his testimony with USC Shoah Foundation. “So we went back on a shipload of wives.”

They did not return to Nuremberg. In Washington D.C., Zetterberg continued to work as a lawyer, but was paid a secretary’s wage -- $2.50 an hour.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.