First they came for

First they came for the Muslims, and we said, “not this time.”

In their third day of protest in certain cities, demonstrators gathered in unity against President Donald Trump’s recent executive order restricting immigration and travel from seven Muslim-majority countries – Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen – for 90 days. The order also suspends the immigration of anyone via the United States’ refugee program for 120 days – including those whose applications, after facing rigorous screening, were already approved – and specifically refugees from Syria indefinitely.

So first they came for the Muslims.

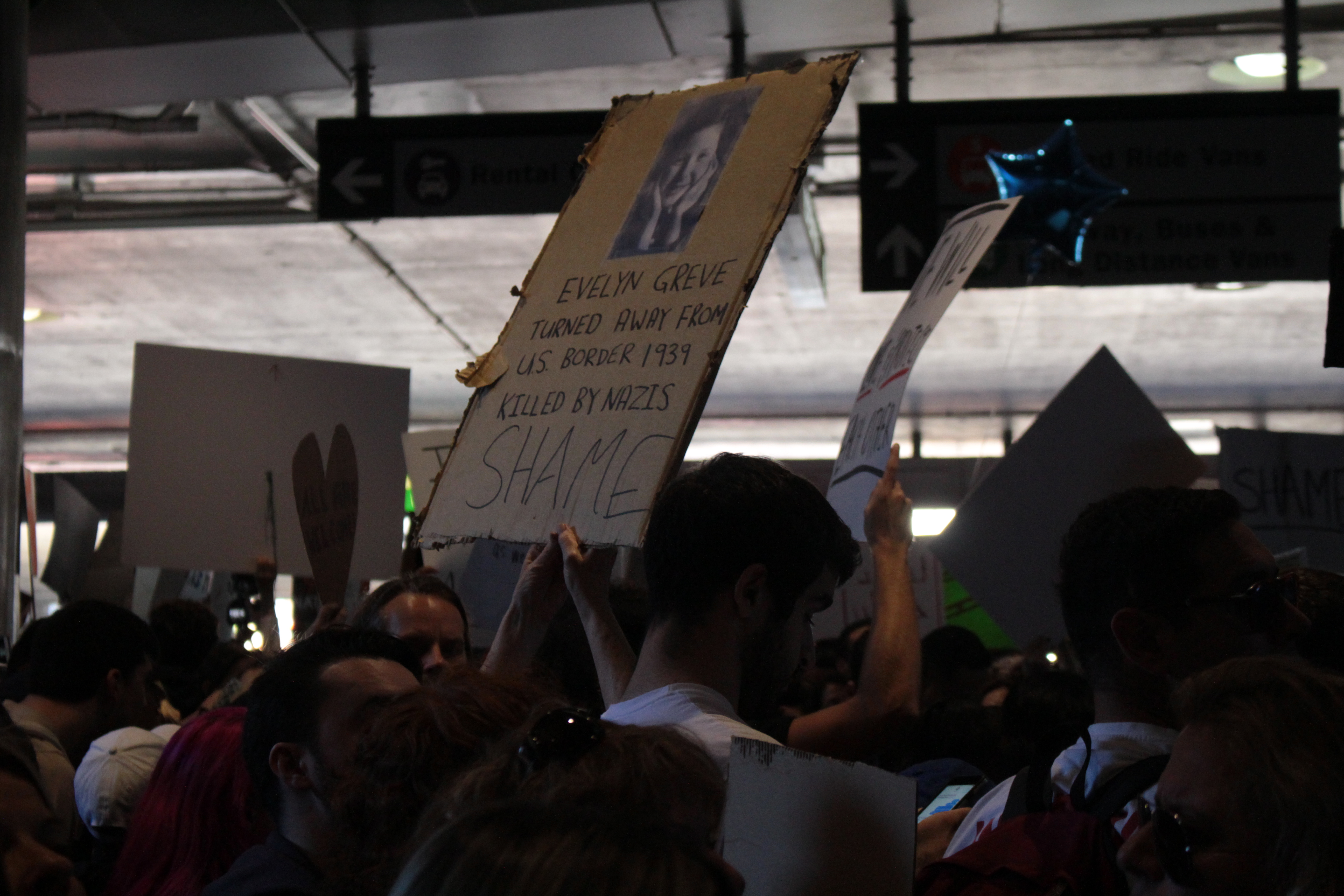

But immediately, the American people spoke out, with sit-ins and chants of “Let them in” and “From Palestine to Mexico, all the walls have got to go;” with attorneys and translators taking up residence in LAX and at JFK and O’Hare, tirelessly filing paperwork on behalf of the detainees and families trapped by the confusing language of the order in an airport limbo; and with posters that translated the megaphone cheers and drums and rage into something more tangible.

Some echoed the chants directly, put Sharpie to cardboard to say “Build love, not walls;” others got more involved and inventive, with calls to “Dump Trump,” to “Ban Bannon” accompanied by crude-but-welcome illustrations; overwhelmingly many had receptive messages for refugees and immigrants, and requests for the release of all in airport detentions.

And several others appropriated a line from Lutheran pastor and theologian Martin Niemoller’s poem “First they came…,” written in the years after World War II, condemning the cowardice and apathy of German intellectuals who sat back and watched the Nazi rise to power and subsequent expulsion of their targets as they moved from group to group:

“First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out–

Because I was a Jew.

Then they came for me–and there was no one left to speak for me.” (United States Holocaust Museum)

The text, according to Niemoller not a poem necessarily, took shape over the course of a couple decades of history and bigotry – much like the heat and seething leading up to the election of President Trump and the passage of his recent executive orders. The immigration ban and plans to loosen regulations for immigrants of specifically Christian backgrounds call up the memories of the Holocaust sign-bearers played off of with their scrawls of “First they came for the Muslims, and we said ‘Hell No’/‘Not Today Satan’/‘Not today mother******’.”

The original quotation became popular after the 1950s, when it took on the widely-recognized poetic form. Since then, it’s been used to encourage civil rights, collective action and unity against anything where a marginalized group is made to suffer because someone else thinks there’s no room for them in their space.

As a reporter at the protest, seeing the posters borrowing from Niemoller’s text pulled me into the realm of opinion, reminded me of the testimony I’ve watched as an intern of USC Shoah Foundation. During World War II, before the poem spread, Nazi Germany came for the Jews. Many people watched, let it happen. But then, some did not. Some took notice and resisted.

Marion Pritchard recalls bringing up the topic of homosexuality at the dinner table and how her father took her aside to discuss the importance of tolerance. She passed away in 2016 at the age of 96. Read our tribute to her. Marion Pritchard a member of the Dutch resistance movement remembers the use of anti-Jewish propaganda when the Nazis invaded the Netherlands. She speaks on how the Nazis used education tools to separate the rest of the population from the Jews. Marion Pritchard a member of the Dutch resistance movement, recounts her experience hiding a Jewish family. In this compilation of clips from Marion's testimony she describes how she killed a Nazi in order to save the lives of the Jewish family she was hiding. Marion Pritchard recalls bringing up the topic of homosexuality at the dinner table and how her father took her aside to discuss the importance of tolerance. She passed away in 2016 at the age of 96. Read our tribute to her.Remembering Dutch Rescuer Marion Pritchard

Marion Pritchard on her early attitude regarding homosexuality

Marion Pritchard on the dangers of propaganda

Language: English

Marion Pritchard confronts Nazi to protect Jewish children

Language: English

Marion Pritchard on her early attitude regarding homosexuality

Language: English

Take rescuer of Jewish children during the Holocaust and donor of testimony Marion Pritchard, who passed away this past December at 96. Known for her eloquence in delivering stories and her righteousness during the war, she was a young social work student when the Germans started relocating Jews in Amsterdam to concentration camps and killing camps in occupied Poland. After witnessing German soldiers taking children away from her town, she became a force in the Dutch resistance, helping families and children hide from Dutch Nazis and providing them with the resources to survive. It’s estimated that she saved around 150 people.

Or my grandfather, who’s not featured in the Visual History Archive and passed away before I came to know him, who experienced the loss of most of his family as a child during the war and very nearly was killed too, had it not been for an older man riding with him in the caravan to a death camp, who told him to run; had it not been for the resistance fighters who found him in the woods and trained him as one of their own, to liberate as many as they could as soon as Russia had the upper hand.

What I’ve learned, looking back at my family history and while working at USC Shoah Foundation, is how to do resistance. That’s how you do resistance. You see injustice and you tirelessly fight against it.

Since the protests across the country, federal judges have struck down the ban, only to be faced with orders from the President and attorney general to uphold the order. Most recently, a federal appeals court rejected the Trump Administration’s request to reinstate the immigration ban. For now, all the legal uncertainty allows more-or-less free travel again.

That’s how you do resistance. You see injustice and you tirelessly fight against it.

The intent of the ban may be pure – safety is a grand aspiration. But I think we can all admit, there’s something fundamentally wrong when infants and children are barred from entering the U.S. for life-saving surgeries; students are not allowed to return to finish their education; families are separated.

Acting out against the Muslim ban is a great step forward, but it can’t be the last step (and it isn’t a step that should be over – there are still people detained, being sent away from the country; students unable to return to school; family unable to reunite). Otherwise, they keep coming for us, and then there’s no one left to stand up for us.

I am the daughter of Jewish refugees from Russia and an intern of USC Shoah Foundation, whose Visual History Archive houses many thousands of testimonies generously donated by survivors of holocaust and genocide. These people have been here before. Their voices are preserved in the Archive. They know where a strong personality can lead a country, and they know what an injustice it can be if we let this escalate so far.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.